Cycling’s progress is easy to spot. Lanes are more common, bikes are better, and cities like Paris and London look more cycling-friendly than they once did. But a new dataset suggests that the decision to ride or stop riding is also shaped elsewhere.

Shimano surveyed 25k people across Europe to understand how cycling is actually experienced today. The results reveal patterns in infrastructure perception, children's safety, and bike maintenance that shape whether people ride or not.

The Data Set

Between September 4 and September 29, 2025, Shimano collected responses from 25 countries and regions. Each country had roughly 1k respondents aged 18 to 79. The sample was nationally representative and weighted by age and gender to reflect real population distributions across Europe.

The survey focused on three areas, cycling infrastructure development, perceptions of children’s cycling safety, and access to bike maintenance services. These topics were selected because they strongly influence whether people cycle and how often.

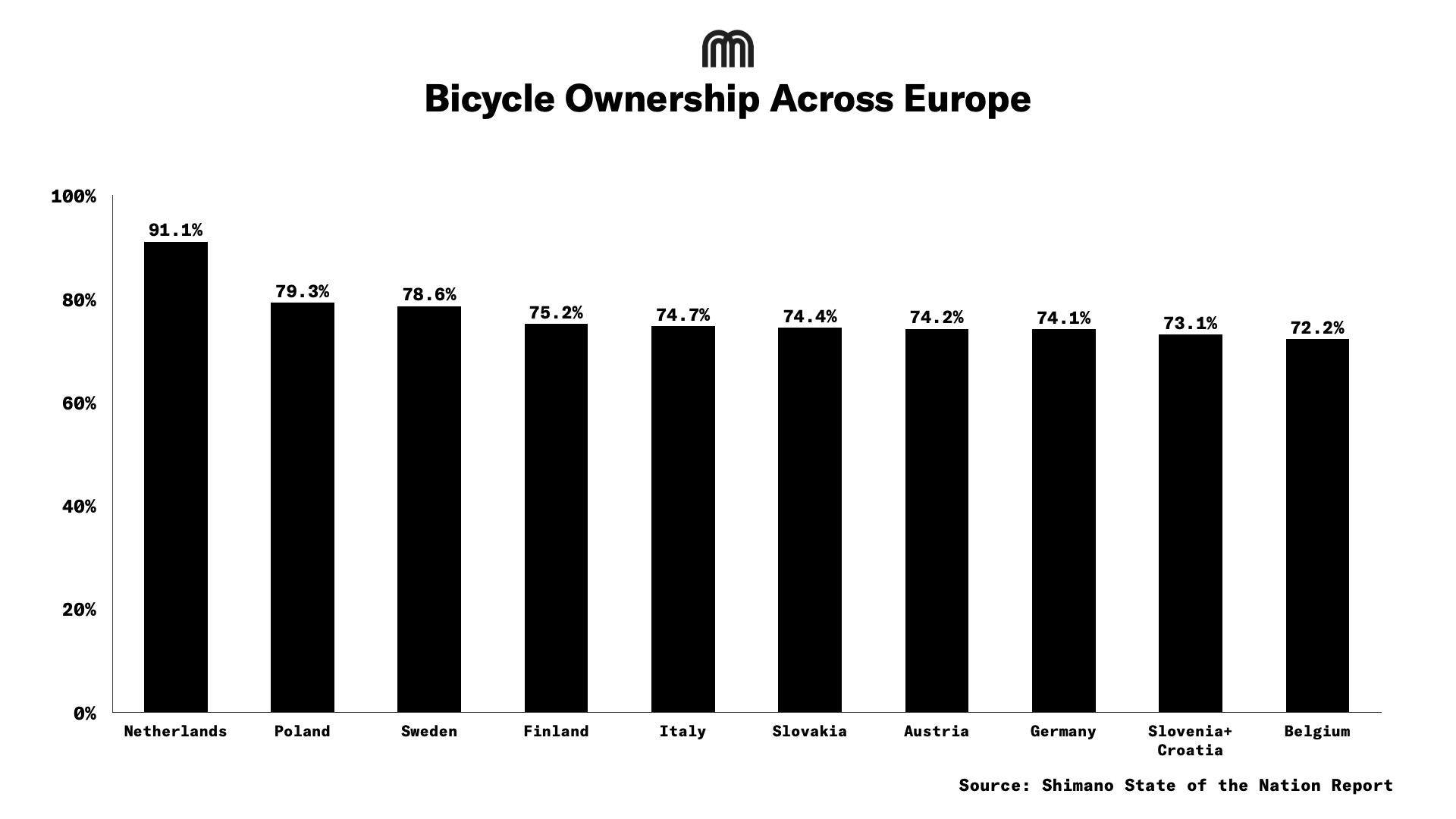

Bike ownership across Europe varies significantly. The Netherlands leads at 91.1%, followed by Poland at 79.3% and Sweden at 78.6%. At the other end, the UK and Ireland report 48.5% ownership, while Portugal stands at 55.9% and Bulgaria at 54.1%.

When asked whether they had ever owned a bike, the numbers rose sharply. The Netherlands reaches 99.7%, Finland 98.4%, and Sweden 98%. Even in markets with lower current ownership, 87% of people in the UK and Ireland report having owned a bike at some point.

The gap between “ever owned” and “own now” points to what happens after people buy bikes.

Maintenance Barriers Keep 121M Europeans Off Their Bikes

Cycling in Europe does not usually end with a crash or a sudden loss of interest. More often, it ends quietly. A bike needs a repair. The shop is far away. The cost feels high. The wait is long. The ride does not happen.

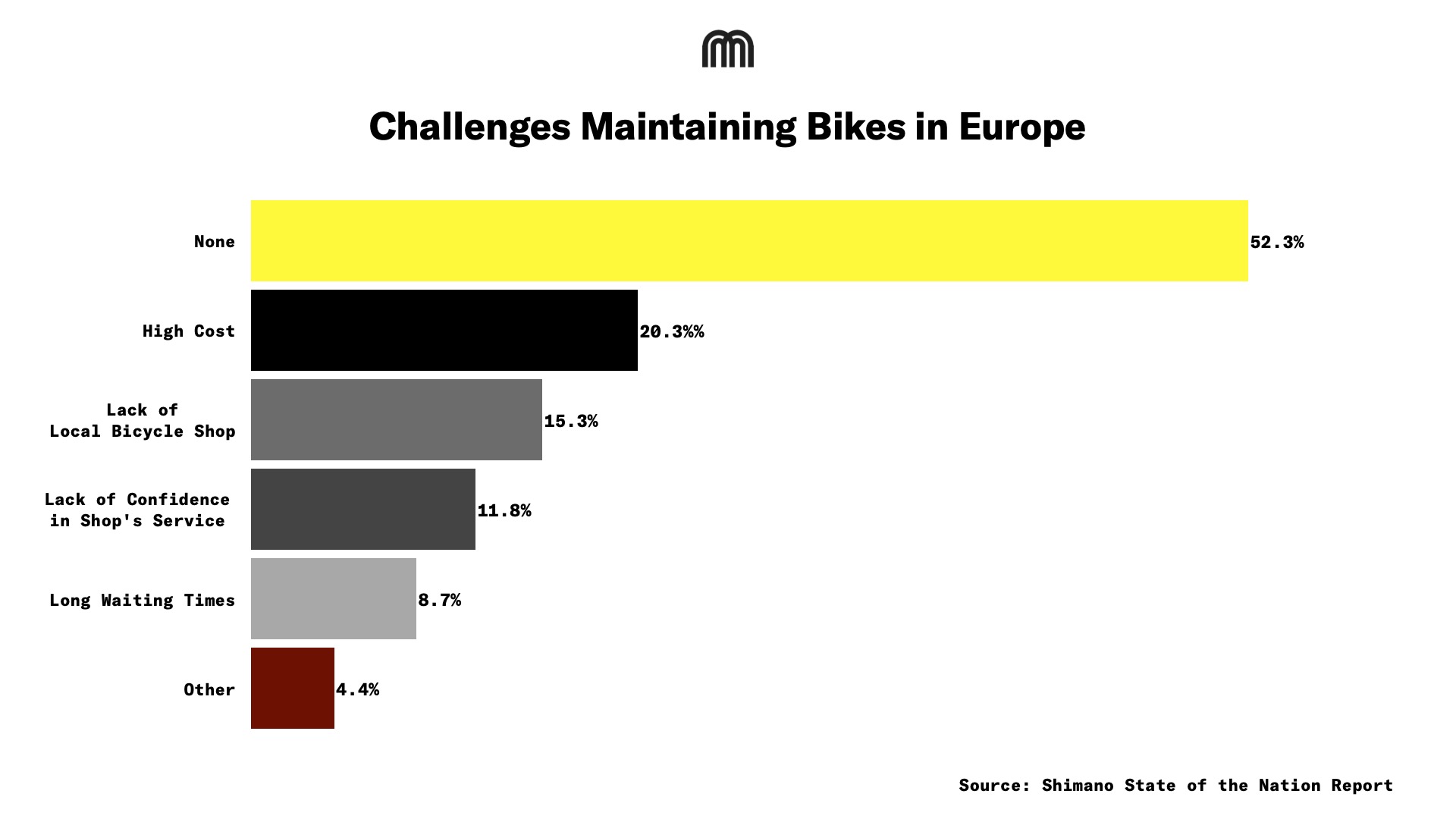

Among Europeans who own or previously owned a bike, 212m people experience barriers when trying to maintain their bicycles. These barriers lead 121m people to cycle less than they otherwise would. Of these, 65m report cycling much less frequently, and 7.6m stopped cycling entirely due to maintenance-related issues.

The most common barrier is trust. 52.3% of respondents who experience maintenance issues cite a lack of confidence in service quality or the skills of mechanics at their local bike shop. Cost follows, with 15.3% identifying high prices as the main obstacle. 8.7% point to a lack of local bike shops or difficult opening hours, while 4.4% cite long waiting times as their primary issue.

The impact varies across countries. Türkiye reports the highest rate of maintenance barriers, with 55.86% of people affected, followed by Romania at 55.62% and Bulgaria at 54.33%. The Netherlands shows the lowest rate at 34.92%, with Switzerland at 40.49% and the UK and Ireland at 40.92%.

When people encounter these barriers, they respond in different ways. 26.93% try to repair their bikes themselves. 21.77% rely more on other forms of transport, while 20.72% cycle less frequently. Others delay necessary repairs (18.16%), stop cycling altogether (16.36%), or avoid longer trips due to safety concerns (15.87%).

Age plays a clear role. Among people aged 18 to 34, 60% experience maintenance barriers. For those over 40, the figure drops to 40%. This concentration among younger cyclists suggests that maintenance access could shape future participation rates.

Perception of Safety for Children

If maintenance shapes whether adults keep riding, perceptions of safety shape whether cycling continues into the next generation.

Across Europe, 37% of respondents say cycling has become less safe for children over the last twelve months. This perception varies sharply by country. Poland reports the most positive shift, with a net +41.04% of respondents saying it has become safer for children to cycle locally. France follows at +40.18%, while Finland reports +33.06%.

At the other end of the spectrum, Greece records the lowest confidence in children’s cycling safety, with a net -28.14%, followed by Bulgaria at -27.16% and the Balkan countries at -22.88%. Notably, the Netherlands, despite its strong cycling culture, also ranks low at -22.67%, reflecting declining confidence rather than absolute safety conditions.

When asked what actually makes cycling safer for children, responses are consistent across borders. 65.27% of respondents cite improved child-friendly cycling infrastructure as the most effective measure. Safety and awareness campaigns follow at 37.95%, while 34.79% point to school and community cycling programs. Financial support for bikes and safety equipment plays a smaller role at 16.22%.

These responses suggest that perceptions of safety are shaped less by education alone and more by what children encounter on the street.

The Infrastructure Expectation Gap

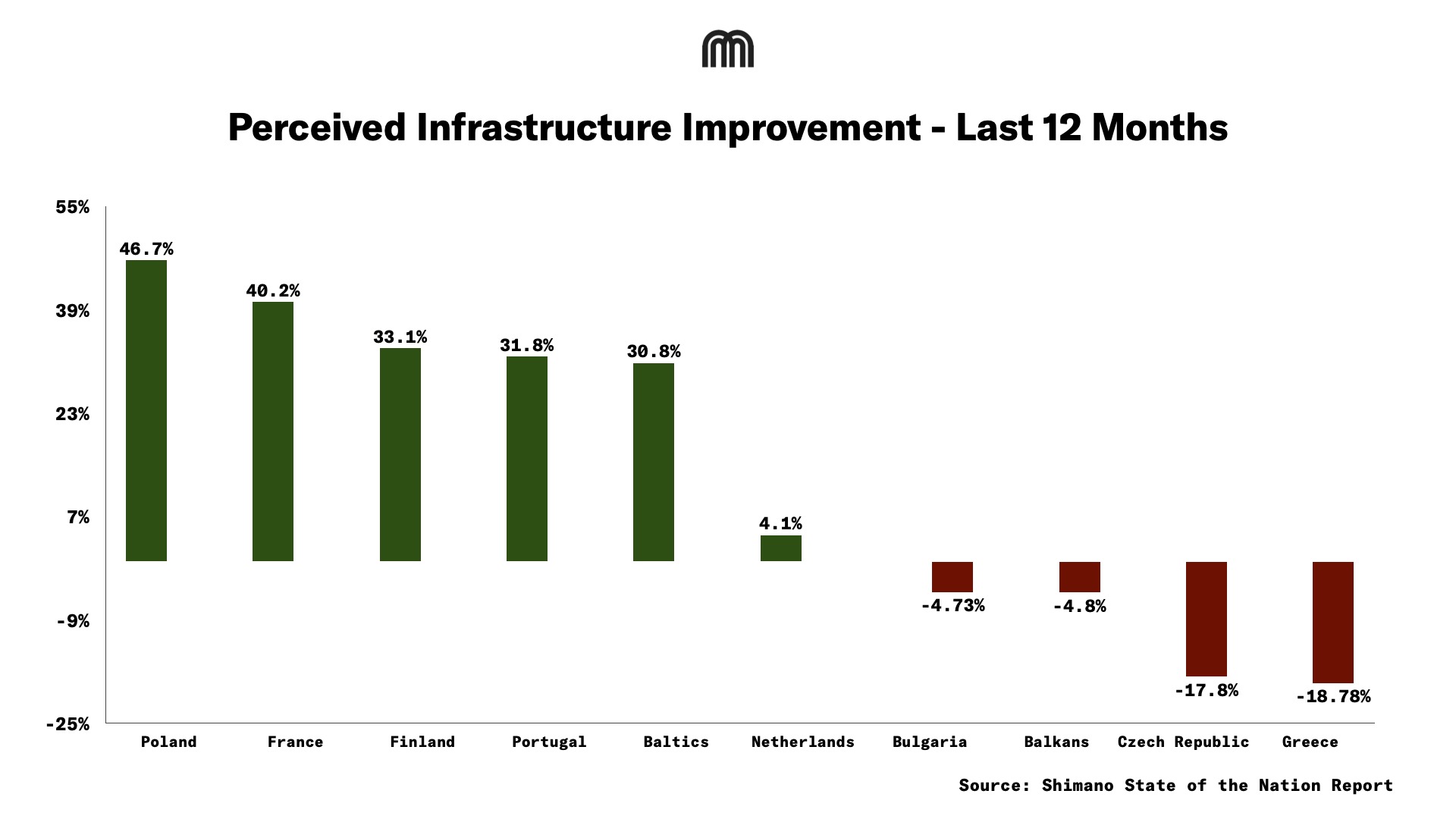

When it comes to infrastructure, the picture is mixed. Across Europe, many people agree that cycling infrastructure is improving, but progress is not felt evenly.

Poland again leads, with +46.67% of respondents reporting improvements over the last year. France (+40.18%) and Finland (+33.06%) also scored high. In contrast, Greece reports a net -18.78%, the lowest in Europe, followed by the Czech Republic at -17.80%.

Some of the lowest scores come from countries long considered cycling leaders. The Netherlands reports +4.10%, while Denmark sits at +7.16%. In mature cycling markets, incremental progress is felt less strongly, and stagnation is perceived more quickly. Expectations rise as infrastructure matures.

This gap between improvement and perception matters. When progress slows in reference markets, they lose their role as benchmarks for what cycling can look like elsewhere.

What the Dataset Shows as a Whole

Taken together, the survey captures three interconnected challenges. Maintenance barriers affect how often people ride. Perceptions of children’s safety influence whether families choose cycling. Infrastructure quality shapes both current riders’ experiences and potential cyclists’ willingness to start.

The patterns are consistent. Younger cyclists face maintenance barriers more often than older ones. Countries newer to cycling infrastructure report stronger perceived improvement than long-established cycling nations. Across all markets, trust and cost remain central to whether bikes stay in use.

Shimano presents this research as a baseline rather than a prescription. Alongside the survey, the company points to initiatives such as NextGen Mechanics, aimed at developing skilled bike mechanics, and the Shimano Mechanics Championship, designed to raise the profile of the profession. A research grant has also been announced for master-level thesis work on topics covered in the study.

The data does not prescribe solutions. It measures where Europeans experience progress and where friction appears. For an industry focused on increasing participation, these measurements matter. They show which barriers reduce cycling frequency and which areas shape confidence.

The survey is expected to be repeated in future years, allowing changes to be tracked over time. Whether maintenance access improves, safety perceptions shift, or infrastructure development accelerates will depend on the actions taken by industry, policymakers, and communities.

What is clear from the data is that many people are not rejecting cycling. They are riding less because keeping a bike running has become harder than it needs to be. The gap between owning a bike and maintaining it now shapes participation across Europe.

Image credit: Shimano

.svg)

%2Bcopy.jpeg)

.svg)

.png)