The urban travel transition has eaten up untold amounts of column inches over the last decade. As people across the globe are turning away from car-centric cities in the name of safety and convenience, micromobility has risen as a solution, with bikes in particular at the forefront.

While some cities achieved this transition long ago (we’re looking at you, Amsterdam) there are many others like Paris and London who are in the midst of this change. The big question, though, is how you go about this in the most effective way. So far, there has been no single consensus, with governments adopting a variety of approaches, ranging from subsidies to designing 15-minute cities.

While undoubtedly a positive force, these initiatives are often complex, multi-faceted, and difficult to measure the effectiveness of. Instead, data suggests there might be a simpler and more impactful way to get people biking: build more cycle lanes.

The evidence is compelling.

Last week, Transport for London (TfL) published its annual Travel in London report. This revealed that daily bike journeys rose from 1.05 million in 2019 to 1.33 million in 2024, a 43% rise. Growth from 2024 to 2025 alone was 12.7%. That’s some serious expansion — so what’s driving this change?

One alluring explanation is the increase in bike lanes. London’s strategic cycle network has expanded dramatically in recent years, rising from 90 km in 2016 to over 431 km in 2025. In the past 12 months 18 new cycleways were added, a 7% increase from the year before.

This is further highlighted by the fact that about a third of cycling in London takes place on cycleways, despite these making up only about 2.5% of the city’s rideable roads and paths.

To rephrase that, people appear to prefer cycling on custom-built lanes. A key reason for this is welfare. The TfL report found that 40% of cyclists travelling on roads without cycle paths felt safe. This is in stark contrast to the 76% who said they felt safe on designated bike paths.

What we’re seeing in these London-centric statistics is broadly simple: bike lanes make people feel safe and, if people feel safe, they’re more likely to cycle.

The impact of dedicated infrastructure on cycling behaviour isn’t just limited to the UK, though, there are plenty of examples of this approach working in other parts of the world.

When it comes to cycle lanes, the Netherlands is far ahead of any other nation. It has the highest total length of cycle tracks (31,000 km) and a 70.5% ratio of cycle tracks to main roads, far outstripping any other country.

Unsurprisingly, the Netherlands also tops the amount of daily cycle journeys in Europe, with 43% of people saying they bike at least once a day. The other countries rounding out the top six are Denmark (30%), Finland (28%), Hungary (25%), Sweden (19%), and Germany (19%).

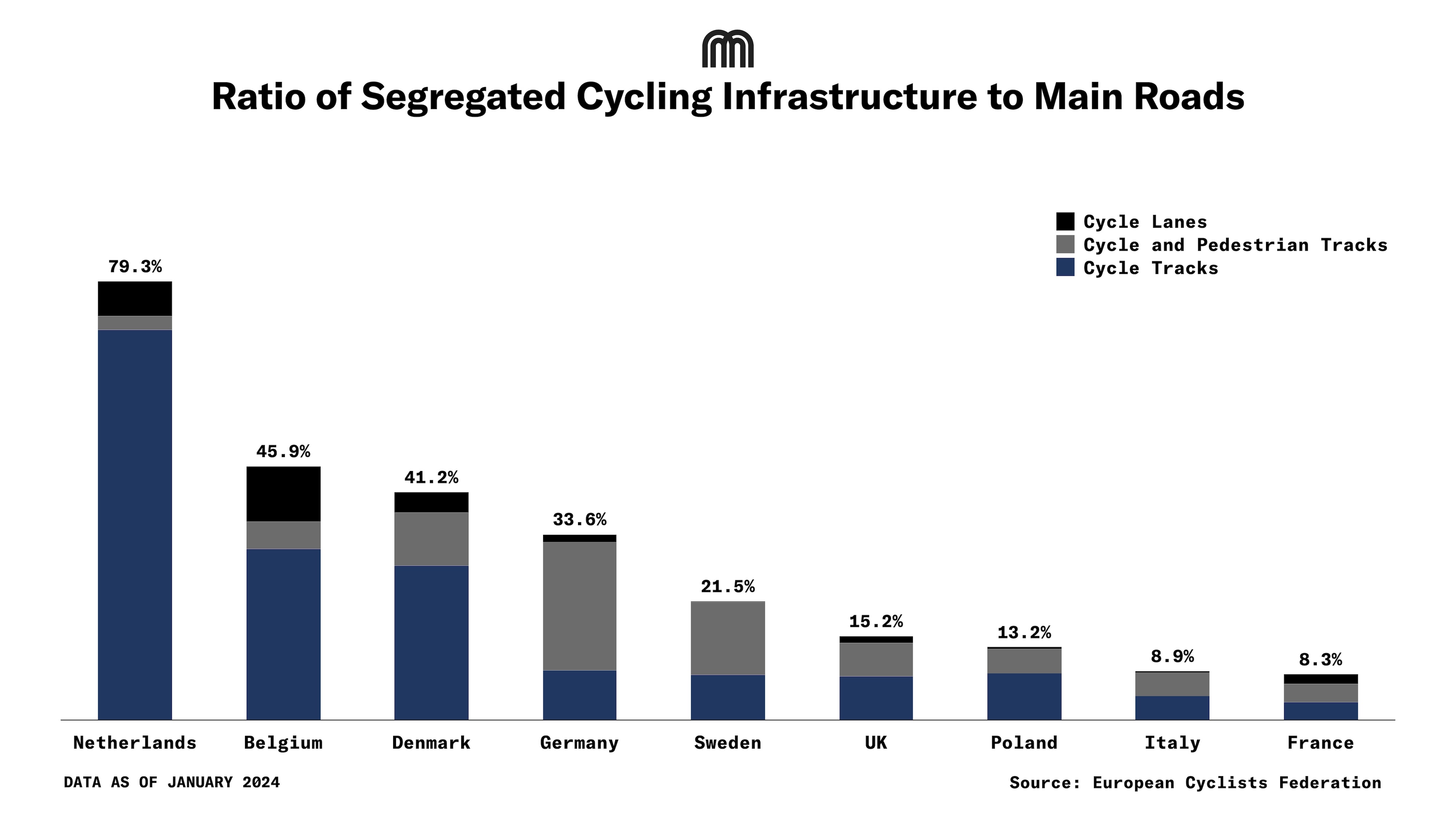

The majority of these countries also score highly on the ratio of biking infrastructure that’s separated from main roads:

There appears to be a direct correlation between people cycling and biking infrastructure. We can drill down even further into this idea.

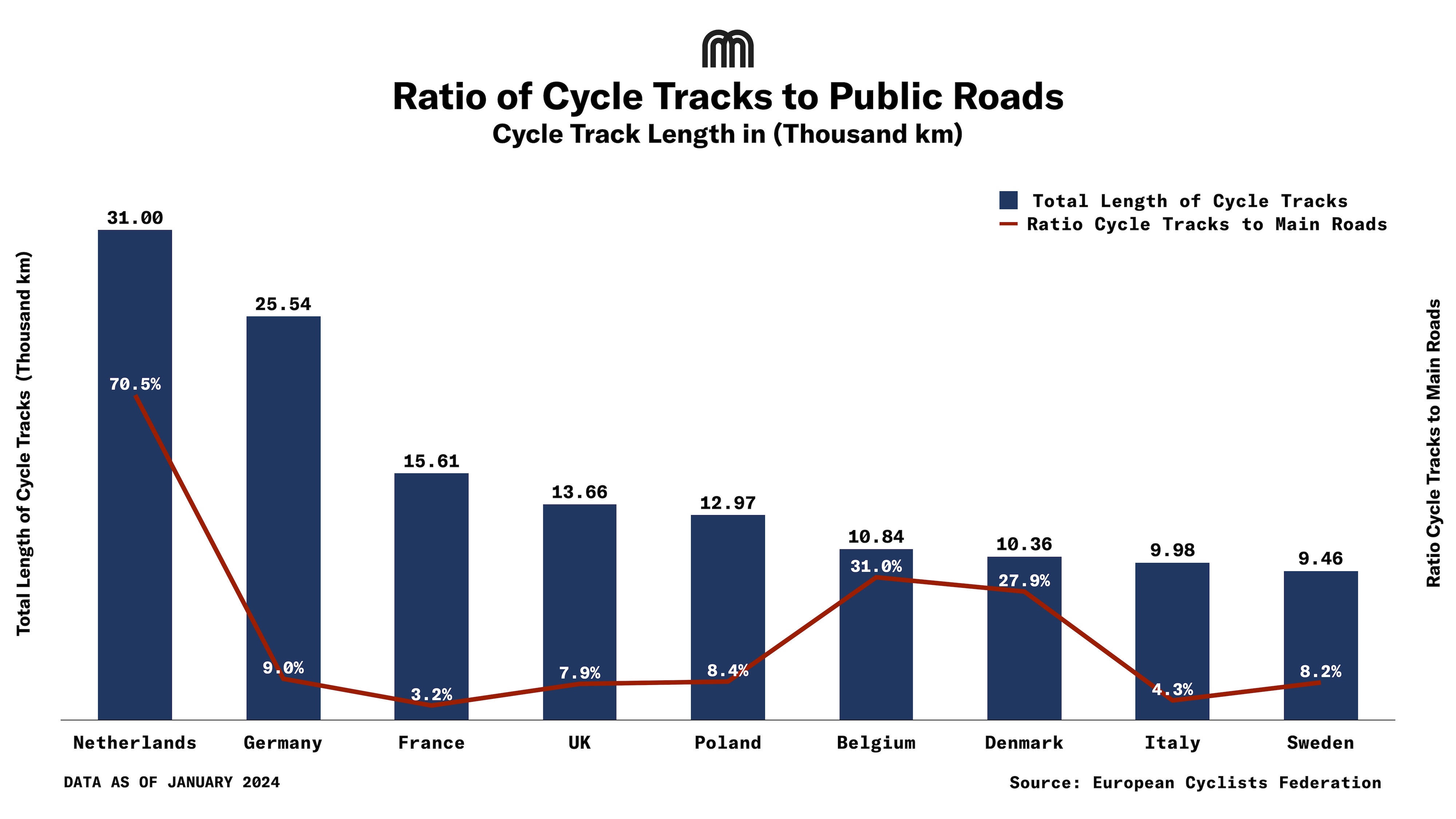

If we recall earlier, despite covering only 2.5% of London’s roads, cycleways constituted a third of bike traffic. Is there a link in other cities? Well, let’s look at the graph below:

At first, this appears to negate our thesis. France and the UK have huge lengths of cycle lanes, yet don’t have the same daily rider numbers as other nations. But the important aspect here is the ratio.

The countries that have a high proportion of cycleways to roads (Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, and Denmark) are nations with high numbers of regular bikers. The key then isn’t the sheer number of cycle lanes, but the ratio of them to regular roads.

If there are a lot of available bike lanes, it’s likely people will bike. We’ve even seen this played out in Paris over recent years.

From 2015 to 2020 as part of the Plan Vélo scheme, Paris built hundreds of kilometres of cycling lanes, forming a cycling network of around 1,000 km across the city. As a result, between 2019 and 2022 riding on bike lanes increased by over 71%. And, in June 2022, the city recorded an all-time high of 1.2m bicycle trips in a single day.

Before we finish, though, a caveat: correlation isn’t causation. In all the countries with high cycling rates, the government isn’t only building bike lanes and leaving cyclists to work the rest out themselves. There are plenty of other initiatives to transition to a cycle-first city, from creating parking infrastructure to introducing subsidies.

The point we want to make though is the best way to get people cycling is, simply, to get people cycling — and one of the biggest indicators of success for this are dedicated biking lanes.

Individuals feel safer when they cycle on well-managed tracks, leading to them cycling more. This can create a cascading effect, where biking is normalised and demystified. These new individuals begin to cycle, immediately feeling safe on bike lanes and the whole process expands.

If cities want people to cycle, they need to build safe places for that to happen. To quote Field of Dreams: “If you build it, they will come." That might’ve been about baseball, but it’s just as true for bikes too.

Cover Image Credit: François-Xavier Chamoulaud, Unsplash

.svg)

%2Bcopy.jpeg)

.svg)

.png)