E-bikes and e-scooters are everywhere. Cities from Amsterdam to Austin have them. Delivery workers depend on them. Commuters use them daily. And as these vehicles become central to how people move, the financial systems that protect riders, operators, and cities are evolving to match.

Insurance sits at the center of that evolution. It is not the most visible part of the micromobility story, but it is one of the most consequential.

Understanding the Risks

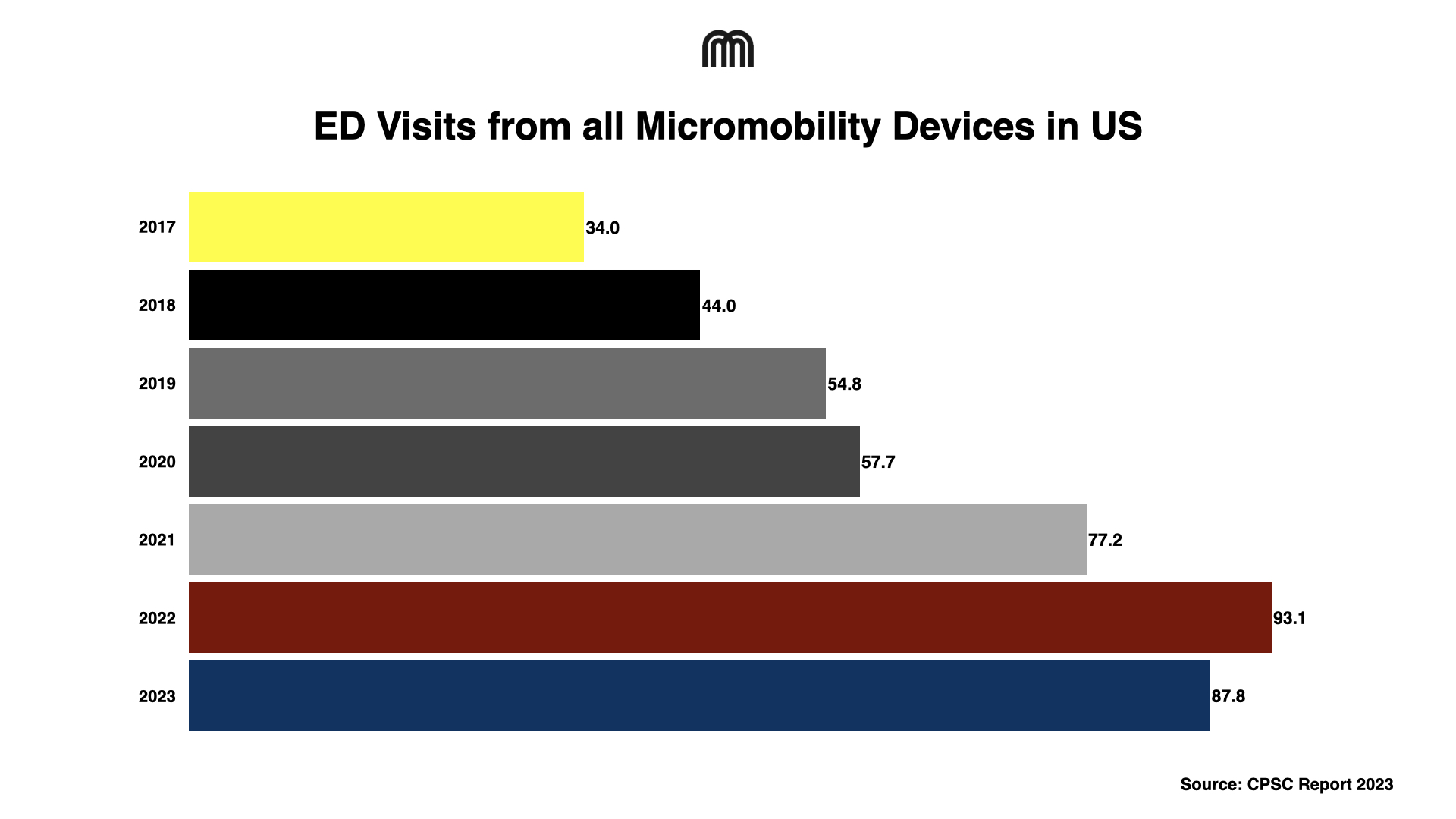

The data shows why this evolution is necessary. Data from the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) indicates that micromobility-related emergency department (ED) visits reached an estimated 448.6k between 2017 and 2023.

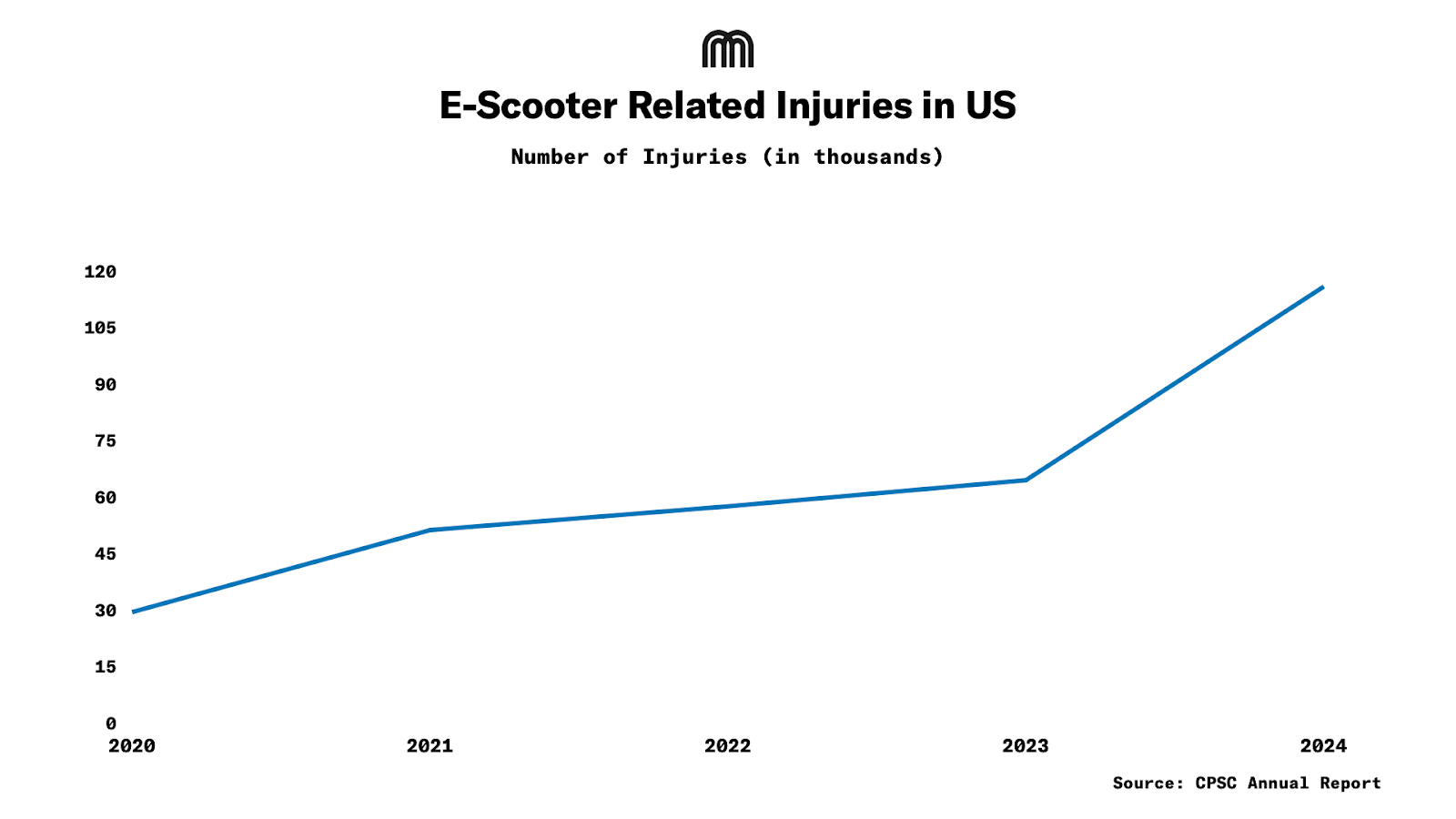

In 2020, e-scooter injuries were approximately 29.3k by 2024, that figure rose to 115.7k. E-bike injuries followed a similar trajectory, increasing nearly 10-fold between 2017 and 2023. Over this seven-year period, the CPSC confirmed 373 fatalities involving micromobility products, with motor vehicle collisions serving as the leading cause of death. In 2024 alone, medical facilities treated ~21k e-scooter-related head injuries.

The Infrastructure Gap

A primary driver of these risks is the mismatch between new vehicles and old streets. Brandon S. Schuh, Senior Vice President and Head of Specialty Insurance at Christensen Group, says that urban design remains a major safety barrier.

"Our current infrastructure system is built for automobiles. So electric bikes, scooters, and other form factors are pushed to the margins and secondary in terms of most regulators' priorities when designing infrastructure and cities and safe user systems. This leads to a safety issue where riders are forced to use infrastructure that's not as safe as what could be used if the city was more thoughtful in their design."

Schuh notes that for fleet operators, the most common risk involves "avoiding or circumventing regular automobile traffic," where a 4k pound car inevitably wins against a 40-pound scooter. This friction has led to a "knee-jerk" legislative response in some areas.

In January 2026, the New Jersey Governor signed a law reclassifying all e-bikes, including Class 1, 2, and 3 models, as motorized bicycles. Under the new rules, every e-bike rider must hold a valid driver's license or obtain a motorized bicycle license, register the vehicle with the state's Motor Vehicle Commission, and carry liability insurance. It is the most expansive e-bike regulation passed by any US state to date.

Regarding recent insurance mandates in New Jersey, Schuh observes: "I think what we’ve just witnessed in New Jersey is a lens into what the future might hold. New Jersey’s requirements for licensing and insurance are aggressive and monolithic in nature, but still in the direction of where I suspect that most cities will take it. It’s not out of line to require insurance for electric bicycles and scooters, however, the process and speed by which they’ve done this is unrealistic and will likely only hurt lower income and immigrant populations who tend to be the primary users in the gig economy."

He adds that isolated laws also create their own insurance problems. When only one territory has a requirement, there is no critical mass for insurers to build a product around, and without the law of large numbers, the economics simply don't work.

The Insurance Evolution

Traditional insurance models, designed for cars or stationary stock, often fail to cover the unique operational realities of micromobility, such as theft away from premises or accidental damage during use.

Tobias Taupitz, CEO and Co-founder of Laka, notes that the risk profile of micromobility vehicles is unique.

“Micromobility sits somewhere between traditional bicycles and motor vehicles, but behaves differently from both. Theft risk is significantly higher than for most motor vehicles, usage patterns are more urban and frequent, and product innovation cycles are faster. There’s also a behavioural dimension: many riders are newer to commuting by bike or e-scooter, which changes risk profiles. Insurers, therefore, need more dynamic underwriting, strong claims handling capabilities, and close partnerships with manufacturers, retailers, and fleet operators.”

Laka uses a collective model where premiums reflect actual monthly claims rather than fixed, rigid rates. Taupitz explains the shift:

“Traditional insurance models often struggle with emerging mobility because risk data is still evolving, which can lead to expensive or rigid premiums. Our collective model allows pricing to reflect real claims experience dynamically, which tends to feel fairer to users. For micromobility riders specifically, the biggest pain points are usually speed of claims resolution, transparency on pricing, and confidence that they’ll be back riding quickly after a loss. Aligning incentives between insurer and rider helps build trust.”

Taupitz believes insurance must become an integrated part of the transport ecosystem. "Insurance needs to move from being an add-on to an integrated part of the mobility ecosystem. As micromobility becomes mainstream, users expect seamless coverage embedded at the point of purchase, leasing, or usage, similar to how travel insurance became embedded in airline tickets. Insurance increasingly becomes part of the infrastructure that makes micromobility viable at scale.”

What claims actually reveal

The claims data tells its own story about how these vehicles are being used.Taupitz notes “Theft still dominates claims frequency, particularly in dense urban environments. That reflects both the value of modern e-bikes and their role as primary transport rather than occasional leisure equipment. For e-bikes, we see theft of batteries emerging rapidly.”

The scale of the problem is significant, in the UK alone, around 74.4k bike thefts were reported to police in 2021, roughly 204 bikes stolen every day, and only 5% of stolen bikes are ever recovered, according to Laka's own research. The actual number of thefts is likely much higher, as most go unreported.

“Accidental damage claims, meanwhile, show how frequently these vehicles are now used for daily commuting, logistics, and family mobility,” he said. These are not recreational devices anymore. The risk profile follows the use case.

Private vs Public Fleet

The insurance approach varies significantly between private ownership and shared public schemes. Shared fleets face higher operational complexity, including vandalism, maintenance logistics, and anonymous user liability.

Brandon S. Schuh highlights the difference: "Public risk is much more challenging than private risk. Public risk brings in all sorts of exposures that the city faces like infrastructure, potholes, right of ways, parking of scooters and infringing upon other peoples' rights as citizens. Where private micromobility is pretty cut and dry... your contractual requirements as a private operator are much more focused on the private contract you have."

Tobias Taupitz also breaks down how liability and operations diverge across the two models:

"Privately used e-scooters usually have identifiable riders, clearer duty-of-care structures, and more predictable usage patterns. Public bike share schemes operate at a massive scale with anonymous users, which changes both liability considerations and operational risk."

"Owned micromobility tends to center around theft protection, accidental damage, and liability coverage for individuals... Shared micromobility, by contrast, is more operationally complex. Fleet downtime, maintenance logistics, vandalism risk, and regulatory compliance become major considerations."

For startups, there is a separate barrier that rarely gets discussed. “A single litigated claim can cost an insurer $200k, which forces high entry costs for new players regardless of their actual risk exposure. Larger operators face the opposite challenge, deciding how much risk to internalise versus transfer to an insurer, and managing the legal spend that comes with that decision,” Schuh mentioned.

Those barriers are not theoretical, they are embedded in how insurance coverage is structured today.

For operators trying to secure coverage, the structural barriers are well documented. A 2023 guide from Christensen Group noted that most cities already require liability limits between $5m and $10m, a significant burden for smaller players that has only intensified as the market matures.

The guide also emphasized that successful underwriting goes far beyond compliance paperwork. High-quality loss run data, a clearly articulated safety philosophy, established relationships with underwriting teams, and having claims handling processes and legal representation planned in advance all materially influence an operator’s ability to secure coverage on workable terms.

Insurers as quasi-regulators

Insurance companies are doing more than just paying for accidents, they are actively driving the industry to be safer.

Schuh describes this dynamic directly: "Insurers can play a major role and do play a major role in batteries. Whether you are looking at a manufacturer or an operator, the insurance companies... will act like a quasi regulator in requiring those clients to meet UL certification, look at their quality control procedures, who is manufacturing the battery, what are the warning, labels instructions look like in terms of storage and any disclaimers or warnings."

Taupitz frames this broader role in terms of ecosystem partnership:

"Insurers can contribute by incentivising high-quality components, supporting safe charging guidance, and working closely with manufacturers on certification standards. Beyond underwriting, insurers increasingly act as ecosystem partners, sharing claims data, helping shape safety standards, and educating consumers."

Building toward scale

The global micromobility market was worth $44.12B in 2020, and it is forecasted to reach $214.57B by 2030. The volume of riders, vehicles, and claims will continue to rise.

Schuh sees that growth forcing maturity. "Across industries, insurance plays a major role in helping immature industries develop their risk management and safety protocols. The more experience an insurance company and industry gets within a particular space, the more refined the requirements tend to get. This happens simultaneously with regulation - and it's this back-and-forth, created over time, that increases safety and awareness and improves risk management."

He also makes a broader point about what is needed to get there, “one of the things that needs to happen is collaboration between insurance, industry, and regulators, and one of the ways to do that is to put in place a standard body and association that’s comprised of private citizens, industry, professionals, regulators, legislators and legal experts, one that is proactive rather than reactive.”

For Taupitz, the end goal is about trust as much as coverage. "Micromobility insurance is increasingly converging with services. Repair networks, theft recovery, resale markets, and lifecycle support are becoming part of the insurance proposition. That shift reflects how central these vehicles are becoming in everyday urban transport."

"Insurance is a trust enabler. Cities, operators, manufacturers, and riders all need confidence that risks are understood and manageable. Well-designed insurance frameworks can accelerate adoption by reducing uncertainty, supporting regulatory acceptance, and encouraging best practices around safety, maintenance, and infrastructure. In that sense, insurance isn't just a financial product,it's part of the foundation for sustainable urban mobility," Taupitz said.

The vehicles scaled first. The infrastructure is following. Insurance is part of that infrastructure, and the industry is now building it in earnest.

.svg)

%2Bcopy.jpeg)

.svg)

.webp)