Welcome to Micromobility Pro, a bi-weekly publication which is part of The Micromobility Newsletter, where we deep-dive into the financials of micromobility companies and share exclusive insights tailored for professionals and members.

Micromobility Europe 2026

The Earliest Bird catches the best deal! So Hurry Now!

Micromobility Europe 2026 brings the global micromobility community to Berlin for two days of ideas, products, and conversations that move the industry forward. Join us on June 2-3, 2026 at Arena Berlin.

Early Bird tickets are available now at €375. Tickets are limited and prices will increase once the Early Bird Sale ends.

Join McKinsey, Rivian’s ALSO, Dott, NextBike, POLIS, Urban Sharing, Navee, CityFi, Valeo, XYTE, Vmax and many others!

[Sponsor/Exhibit] | [Speak at the Event] | [Exhibit as a Startup] | [Get A Free Pass]

And to find all about Micromobility America | Nov 11-12 | Palace of Fine Arts, SFO - HERE! (Limited Launch Tickets are on sale at $199)

Contents:

- Introduction

- The “Mamachari” Foundation

- The First Wave of Sharing

- LUUP and the Utility‑First Expansion

- The Regulatory Bottleneck

- Lime’s Adaptation

- The Infrastructure Paradox

- Built on What Already Worked

Introduction

Japan often sits in a unique position in the global transport conversation. It is a country famous for its high-tech trains and futuristic image, yet its streets are filled by a piece of technology that hasn’t changed much in decades, the bicycle.

Japan started from a different baseline. Here, cycling wasn’t a ‘movement’ that needed to be sparked, it was already how millions of people moved.

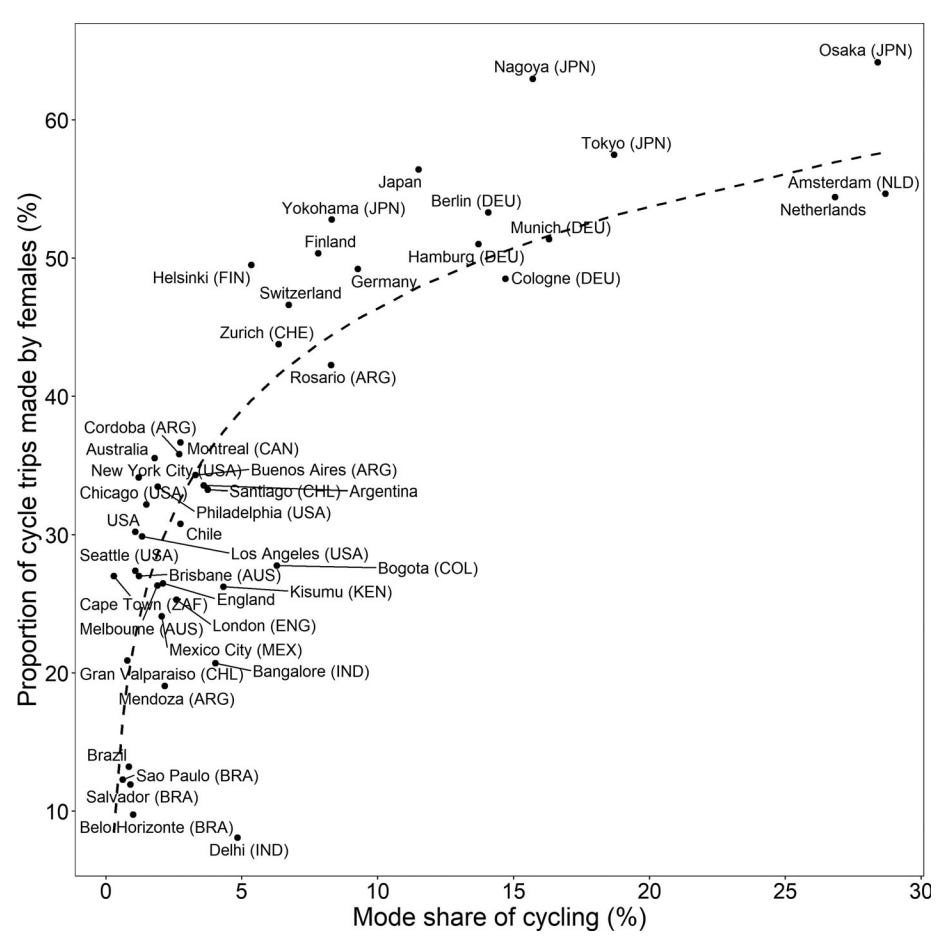

In a 2021 study spanning 17 countries across six continents, Japanese cities stood apart. Osaka, Tokyo, and Nagoya have the highest proportion of female cyclists in the world, often surpassing even the Netherlands and Germany. In Tokyo, women make up 57% of all cyclists. In Osaka, that figure climbs higher at 64%. This wasn’t an anomaly. It was the result of decades of urban evolution shaped by a bicycle that most of the world has never heard of.

Japan has spent decades building a cycling culture rooted in utility, not sport. This article takes a deep dive into how Japan’s unique history paved the way for its modern micromobility boom, a market that has reached a staggering USD 4.4B in 2025.

The “Mamachari” Foundation

The mamachari. The name translates as “mom’s bike,” and that tells you everything about its purpose.

Before the mid-1950s, women’s bicycles were heavy machines weighing between 22 and 24 kg. High centers of gravity restricted their use primarily to younger women. Then 1956 brought the “Smart Lady,” a lightweight model with a low center of gravity and a step-through top tube. Women wearing skirts or dresses could mount easily and ride with stability. The bicycle transformed into a utilitarian workhorse for hauling groceries and ferrying children.

The timing mattered. Post-war urban reconstruction created dense city centers where car ownership remained limited. The bicycle solved the “last mile” gap between transit hubs and homes. By the 1960s and 1970s, cycling became standard for reaching railway stations, shopping, and transporting children to daycare. Cycling stopped being recreation. It became a vital social infrastructure.

As Luup, a leading Japanese micromobility provider, explains, this created something unique: “Bicycles have long been a deeply rooted mode of transportation in Japan, used on a daily basis. A unique cultural aspect of Japan is that bicycles are established as essential infrastructure for mobility, independent of the recent global eco-conscious or health-oriented trends.”

When electric-assist technology arrived in the 1990s, Japan’s cycling culture was already fully established. Yamaha released the world’s first electric-assist bicycle in 1993. Panasonic and Maruishi Cycle followed in 1998 with the first electric mamachari. These weren’t sold as fitness equipment. They were practical tools for parents and the elderly to navigate steep hills while carrying heavy loads.

Terry Tsai, Lime’s Japan Country Manager, one of the global micromobility operators now active in Japan, notes how this foundation influences today’s market: “Japan has some of the highest rates of female cycling in the world, driven by the widespread use of practical utility bicycles like the mamachari. Lime designs its vehicles in house with shared use and accessibility in mind. Shared e-bikes like LimeBike, with step-through frames and practical features, are well suited to everyday trips and align more closely with how many women already move around cities.”

The First Wave of Sharing

Japan’s foray into shared micromobility began in April 2011 when NTT Docomo launched its original sharing business in Yokohama. Unlike the pedal-only fleets common in the West, Japan’s first wave relied on electric-assist bicycles to accommodate the country’s aging population and hilly urban terrain. By February 2015, Docomo Bike Share operated as a standalone entity, scaling to 7.3k bicycles and 700 ports across 25 bases nationwide by 2018.

The first wave succeeded because it tapped into the pre-existing mamachari culture. However, growth faced constraints. Operating costs were substantial, covering everything from electricity to the patrol personnel required to rebalance fleets.

While Docomo focused on central urban wards like Chiyoda and Minato, Hello Cycling, a SoftBank group company, pioneered suburban and residential expansion. Hello Cycling’s strength lay in its massive distribution. By 2025, it maintained a network of 11k stations, many situated outside convenience stores to solve first- and last-mile gaps.

LUUP and the Utility‑First Expansion

In May 2020, LUUP launched its service using electric-assist bicycles. Founder Daiki Okai‘s mission was to build social infrastructure that makes the entire city “a station front.” The strategy addressed Japan’s reality as a public-transport powerhouse with a railway-centric mobility system. Proximity to train stations often results in higher rent and concentrated commercial value. LUUP aimed to fill the gap.

Luup describes the vision: “Our mission is to create an infrastructure that turns the entire city into an extension of the station area. This mission is grounded in the reality that Japan is a public-transport powerhouse with a highly railway-centric mobility system. By shortening a 20-minute walk or transfer into a journey of just a few minutes, we effectively expand stations’ catchment areas and enhance the overall value of the city.”

The company expanded to include e-scooters in April 2021. This multimodal approach recognized that vehicle choice depends on the rider’s immediate needs rather than preference for specific technology.

As Luup explains: “Users flexibly choose vehicles based on their outfit or purpose: opting for e-bikes when carrying heavy loads, or e-scooters when wearing skirts or suits, or when they want to avoid sweating.”

Every design detail aimed to foster daily habits among a broad demographic.

By April 2023, LUUP’s footprint spanned more than 3k stations across Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, Yokohama, Utsunomiya, and Kobe.

In November 2025, LUUP introduced the seated e-scooter, featuring “a seat and cargo basket, developed to answer the needs of those uncomfortable with standing rides or pedaling, and to facilitate carrying luggage.”

Luup says, “Since our service launch, LUUP has adopted a compact vehicle design with a low center of gravity that is easy for persons of short stature to handle,” Luup explains. “Additionally, by adopting color schemes that blend naturally with the cityscape and daily fashion, we believe our service has been accepted by a wide range of people as a daily mode of transport, regardless of gender.”

In November 2025, LUUP secured approximately $29m (¥4.4B) in equity and green loan financing, bringing its total capital raised to roughly $143m (¥21.4B). Currently, the service is being rolled out in 12 cities across Japan, including Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, and Kyoto, with over 12k ports and more than 30k electric kick scooters and electrically assisted bicycles in operation.

LUUP’s expansion was rapid. The service launched in May 2020 with just 50 e-bikes and approximately 50 stations. By February 2026, that footprint had grown to over 40k vehicles and approximately 16k stations nationwide, making LUUP one of Japan’s largest shared micromobility services.

The Regulatory Bottleneck

For years, legal barriers limited the growth of shared e‑scooters. Until mid‑2023, e‑scooters were treated as motor vehicles, requiring licenses, license plates, and helmet use, while prohibiting use of bicycle lanes. These rules created friction for casual users and tourists.

That changed on July 1, 2023, when Japan revised the Road Traffic Act and introduced a new vehicle category - Specified Small Motorized Bicycles. Under the new rules, riders aged 16 and older can use e‑scooters without a driver’s license. Speeds are capped at 20 km/h on roads, with a sidewalk mode limited to 6 km/h and indicated by a flashing green light. Helmets are encouraged but are no longer mandatory.

The impact was immediate. LUUP notes, “In the early days, e-scooters were primarily used for recreation due to their novelty. Today, however, the vast majority of usage for both e-bikes and e-scooters is for everyday transportation. Currently, over 80% of all rides are for short-distance daily travel, including commuting to work or school, daytime business travel, and shopping. We see this as evidence that LUUP is beginning to take root as a new form of transportation infrastructure in Japan.”

Lime’s Adaptation

Lime entered the Japanese market with e-scooter operations in 2024, then executed a major strategic expansion on September 3, 2025, by launching the “LimeBike” and partnering with SoftBank-backed HELLO CYCLING. This collaboration marked the first integration between a global e-mobility provider and a Japanese domestic service, granting Lime riders access to a network of over 11k stations and 50k vehicles nationwide.

While Lime is a global giant, having “powered more than 1B rides in nearly 30 countries,” their approach in Japan had to be highly localized. Terry Tsai explains how their vehicle design now reflects Japan’s cycling culture: “Lime designs its vehicles in house with shared use and accessibility in mind. Shared e-bikes like LimeBike, with step-through frames and practical features, are well suited to everyday trips and align more closely with how many women already move around cities. As the market evolves, this type of vehicle provides an option for all riders using shared micromobility in Japan.”

Operationally, Lime departed from its Western “free-floating” model to adopt designated parking ports. Terry Tsai describes the distinction: “Operationally, the biggest distinction is the use of designated parking ports. Unlike many European or North American cities where free-floating or hybrid parking has historically been common, shared micromobility in Japan is designed around clearly marked parking locations, typically near stations, commercial areas, and key destinations. Trips begin and end at these ports.”

This approach reflects an understanding of the cultural norms that differentiate Japan from Western markets. “Culturally and behaviorally, Japanese riders place a strong emphasis on not inconveniencing others, which drives higher compliance with parking and riding rules and very low levels of vandalism,” Tsai notes.

He continues: “Finally, the role micromobility plays is different. In cities like Tokyo with abundant public transit options, shared vehicles are primarily used as an extension of walking and public transport, solving first- and last-mile gaps, rather than replacing longer trips.”

The Infrastructure Paradox

Japan’s cycling culture developed without the protected bike lanes that Western advocates consider essential. In Tokyo, where bicycles account for roughly 16% of all daily trips, only 305 km of the 18,716 km road network, a mere 1.6%, features any form of cycling infrastructure.

This paradox stems from a 1970 emergency amendment to the Road Traffic Law. During the post-war motorization boom, car-related fatalities involving cyclists rose sharply. In a pragmatic but temporary move to protect vulnerable users, the government permitted cyclists to ride on footpaths. The sidewalk became a refuge for “mobilities of care,” particularly mothers transporting children on mamachari bikes. Because cyclists felt safer on footpaths than on roads dominated by cars, the practice became deeply ingrained.

Operators are acutely aware of this challenge. Luup notes: “In reality, physical infrastructure development is actually lagging behind. Most sharing stations are located on private property, and the development of dedicated bicycle lanes has hardly progressed. While fostering a safe culture and social norms is certainly important, we feel that the importance of physical infrastructure expansion is growing year by year for the further development of micromobility in Japan.”

In the absence of physical lanes, operators must rely on technology and trust.

Lime emphasizes that “safety informs everything we do at Lime,” from vehicle maintenance to rider education. Tsai explains their proactive stance: “We also use technology and vehicle design to proactively address safety and sidewalk use, rather than relying on enforcement alone.”

Remarkably, as of 2012, Japan’s lack of segregated lanes had not resulted in a safety crisis. Tokyo’s cyclist casualty rate per 100k inhabitants sat at 0.27, lower than Denmark (0.47) and significantly lower than the Netherlands (1.20), despite those nations possessing world-class segregated networks. This unconventional safety record is attributed to rigorous traffic calming measures and a social environment where riders prioritize attentive behavior.

The Paradigm Shift Ahead

Japan is now attempting to resolve this paradox through a shift intended to bring bicycles back to roads and reduce pedestrian-cyclist conflicts on sidewalks. The Tokyo Metropolitan Government has committed to expanding the cyclable network to 900 km by 2030.

In April 2026, a new “blue ticket” system will allow police to issue on‑the‑spot fines for 113 cycling offenses, including phone use while riding and dangerous sidewalk cycling. As regulation tightens, policymakers face a balancing act, improving safety while preserving access for riders who have relied on shared spaces for decades.

Built on What Already Worked

Japan took a different route to build its cycling culture. No massive infrastructure projects. No government master plans. Instead, practical necessity met urban density and cultural acceptance, creating a situation where cycling became normal for everyone, particularly women.

The mamachari symbolizes this approach. It’s not a performance bike or a status symbol. It’s a tool that solves real problems for real people doing everyday tasks.

Modern micromobility services are building on this foundation rather than replacing it. E-bikes and e-scooters offer additional options that complement existing behavior. They extend the reach of public transport. They give people flexibility to choose the right vehicle for each trip.

For operators who understood Japan’s unique culture, adaptation was key. Terry Tsai emphasizes this approach to trust and responsibility: “Public trust and safety perception are critical in Japan, they are what enable micromobility to operate and grow. By prioritizing responsible operations and visible compliance from day one, Lime is well positioned to meet Japan’s high expectations for safety, order and reliability, and to earn long-term community acceptance.”

What happens next depends on infrastructure investment, and continued regulatory clarity. The cultural foundation is solid. The market is growing. The challenge now is scaling thoughtfully without losing what makes Japan’s micromobility culture unique.

Terry Tsai sees integration as the next evolution: “We’re seeing a shift from micromobility being seen as ‘nice to have’ to being a vital part of how cities function. The next evolution in Japan is about integration, bikes and scooters working alongside public transport and active travel infrastructure to form one connected system.”

That vision extends beyond urban convenience. As Luup notes “This approach also directly addresses Japan’s structural challenges, including an aging population and a severe shortage of drivers. Micromobility sharing, which enables independent travel without the need for a driver, is expected to become indispensable infrastructure for sustaining regional mobility in both urban and rural areas.”

Japan’s micromobility story began with a simple utility bicycle designed for mothers. Decades later, that same utility-first philosophy is shaping how the country integrates electric bikes and scooters into its urban fabric. The technology has evolved, but the principle remains, build what people actually need and they’ll use it every day.

Got your micromobility moment to share? Email us at press@micromobility.io

Loving the vibe? Hop on and ride with us! Subscribe!

Twitter | YouTube | LinkedIn | Instagram | Blog | Podcast

Image credit: Sean Barker on Unsplash

.svg)

%2Bcopy.jpeg)

.svg)

.png)

.png)

.png)