Electric micromobility vehicles look simple: two wheels, a motor, and a frame. But their ability to operate day after day is governed by a far more sensitive component: the lithium-ion battery. Unlike motors or frames, batteries are constrained not just by wear, but by environmental conditions that fundamentally change how they behave.

Cold weather is one of the few external factors that operators cannot engineer away.

When temperatures drop, range is not the only thing that’s affected. It changes how fleets are charged, deployed, maintained, and even staffed. Across operators, OEMs, and battery suppliers, winter exposes a shared reality: battery chemistry sets limits that software and logistics can only partially manage.

To understand how the industry responds to these limits, we spoke directly with manufacturers, operators, and long-time micromobility leaders working in cold-weather markets.

The Chemistry of Cold

Lithium-ion batteries operate efficiently only within a narrow temperature range. As temperatures drop toward freezing, the electrolyte inside the cell becomes more viscous, slowing lithium-ion movement between the anode and cathode. This increases internal resistance and leads to voltage sag under load.

From a technical perspective, this manifests as reduced usable capacity and misleading state-of-charge readings. From a rider’s perspective, it feels like shorter range, weaker acceleration, or unexpected shutdowns.

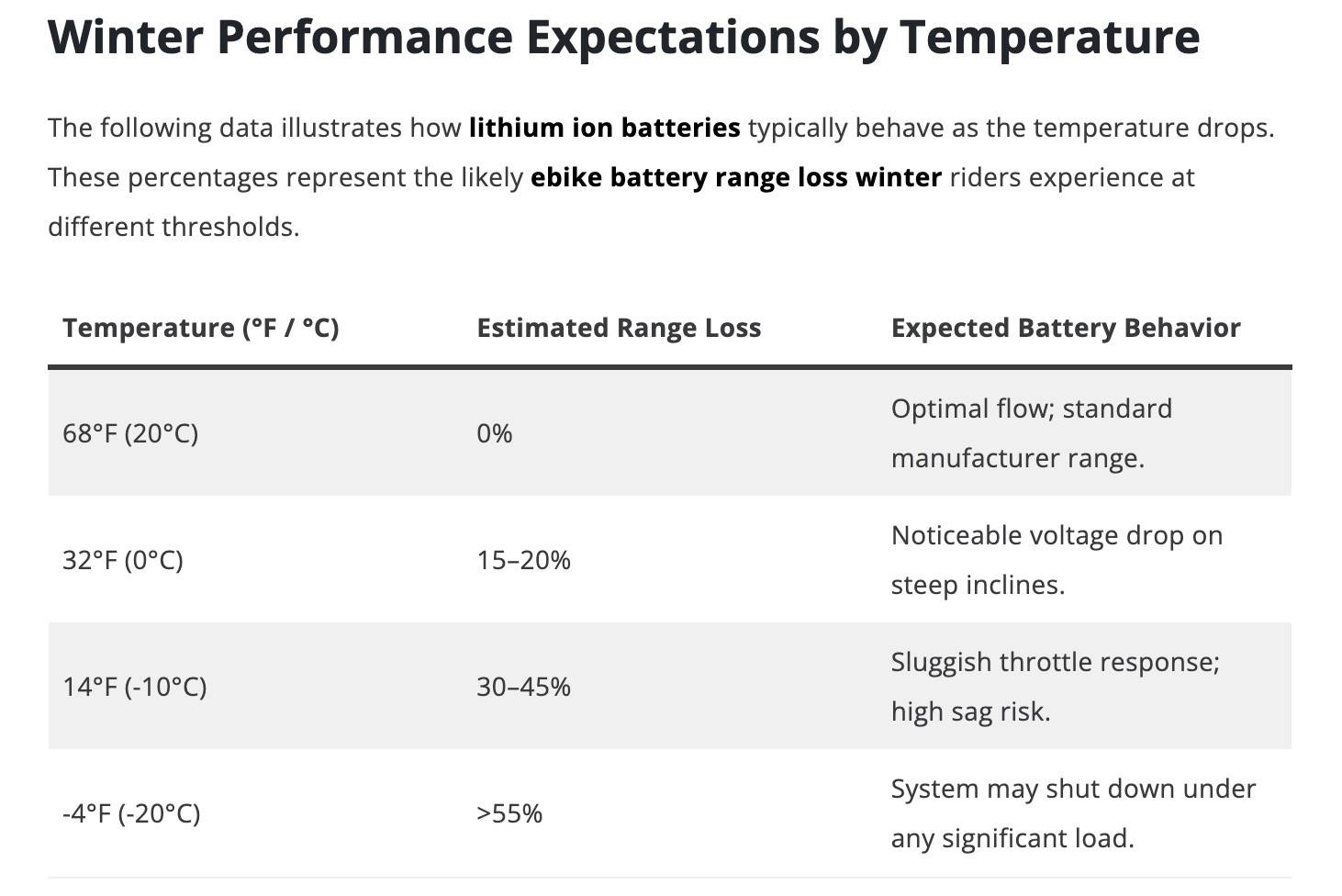

Studies and field observations show usable capacity losses of 20-50% in cold conditions, depending on temperature, discharge rate, and battery age.

Navee explains the underlying physics:

“Cold temperatures reduce battery activity and slow electrochemical reaction rates, leading to a significant increase in internal resistance, especially at low state of charge and low temperature, where resistance can increase by more than ten times. From a user perspective, this results in reduced power output and shorter range.”

The most severe risks appear during charging. Charging lithium-ion batteries at or below 0°C can trigger lithium plating, a process where metallic lithium deposits on the anode surface instead of intercalating safely into graphite. Over time, this accelerates capacity loss and creates internal safety risks.

Olivier Hébert, Head of R&D - Hardware and Embedded Software at VanMoof, emphasizes how unforgiving this boundary is:

“Charging is especially critical because it can cause irreversible damage when done at temperatures below which the cells are designed to be used at. In normal li-ion cells, that happens at 0°C.”

Battery Management Systems (BMS)

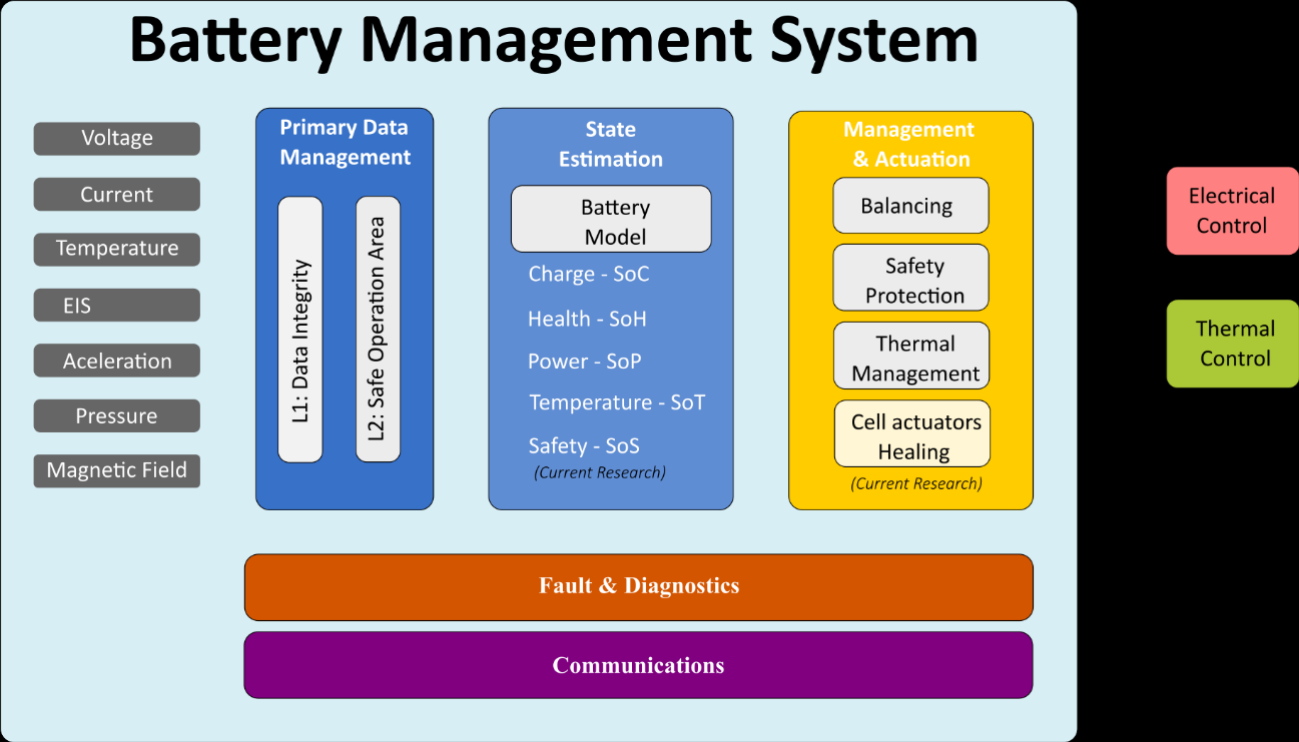

Because battery chemistry can’t be changed, modern micromobility vehicles rely heavily on Battery Management Systems (BMS) to operate safely.

In winter, BMS becomes especially important. It constantly monitors battery temperature, voltage, and charge levels, and steps in when conditions fall outside safe limits.

A recent state-of-the-art academic review maps how these sensing, estimation, and control functions are implemented across modern battery management systems, illustrating how safety and performance are enforced in real time.

Okai puts this control logic in simple terms: “During winter operation, the BMS determines whether the battery meets the operating environment by detecting the temperature environment the battery is in. If it meets the operating environment, the battery is allowed to operate; if not, the battery circuit will be forcibly cut off to prohibit operation.”

This control applies to both charging and discharging. Discharging a cold battery too aggressively can trigger voltage collapse or long-term damage.

VanMoof highlights the need for precision at the edge of operating limits:

“We can discharge a charged battery well below 0°C, but then the available energy is much lower and needs to be determined correctly by the on-board algorithms, otherwise the range estimation will be very incorrect.”

Navee adds that poor control creates lasting safety risks:

“Charging or discharging at high currents in sub-zero conditions can lead to lithium dendrite formation, which poses serious risks to both battery safety and cycle life. A well-designed BMS can actively prevent these conditions through temperature- and SOC-based protections.”

Accurate estimation matters as much as protection. If the BMS miscalculates usable energy, vehicles may shut down unexpectedly even when the battery appears charged.

Designing for the Cold

Battery pack design has evolved as fleets expanded into colder regions. Sealed enclosures, improved insulation, and better moisture protection are now standard. These measures slow heat loss when vehicles remain parked outdoors.

But insulation only delays exposure, it cannot prevent batteries from eventually reaching ambient temperatures during prolonged cold spells.

True low-temperature operation remains rare and costly. Okai explains:

“There are also a small number of special cells that can be used at low temperatures, but they are expensive. For example, some power sources used in polar scientific research equipment or space equipment.”

VanMoof points to similar trade-offs:

“Specific cell chemistries can be designed for better low-temperature performance, but they are usually either more expensive or have less capacity in normal ambient temperatures.”

Some OEMs explore active heating. Large electric vehicles use liquid or air-based systems. In two-wheeled micromobility vehicles, manufacturers often rely on heating films to warm batteries before charging. These systems still require controlled environments and add cost, complexity, and energy draw.

When Cold Becomes an Operational Problem

For operators, winter is not just a performance issue. It is an operational one.

Matthieu Faure, VP Brand & Communications and founding team member at Dott, describes how cold weather reshapes daily workflows:

“Batteries have a narrower temperature range for charging than for operation. While they can typically power a vehicle between -20°C and 60°C, charging is usually only possible when the internal temperature is between 0°C and 40°C.”

This creates what Dott calls a “winter workflow”:

“Arrive at the warehouse → Wait for 2 hours (to reach T > 0°C) → Charge → Store → Back in the city.”

That waiting period forces changes to staff scheduling, warehouse throughput, and shift planning. It adds time without adding energy.

Cold also reduces the number of kilometers extracted from each battery swap cycle:

“Batteries become less efficient in colder temperatures, affecting the usable range of the battery’s capacity. This decreases the number of KM’s we get from each battery swap cycle.”

Dott also adjusts fleet size in winter. Lower demand allows operators to deploy fewer vehicles, hold more spare batteries, and account for longer charging and handling times. Vehicle inspections also intensify, with attention to corrosion caused by road salt and moisture.

Beyond batteries and charging logistics, winter also applies pressure across broader operational economics. Andrew Miles, former Regional General Manager at Veo and former VP of Strategic Projects at Joyride, shared that cold weather reduces overall efficiency while demand simultaneously softens:

“Weather takes a huge toll on operational efficiency, and demand goes down in the colder weather months. Rides become shorter, and the revenue generated per day per device is lower.”

“Cold weather also affects how fleets move. While e-bikes, cargo e-bikes, and e-quads work well for operations in warmer months, limited weather protection reduces their usefulness in winter, increasing reliance on enclosed vehicles.”

Miles also notes that while battery and BMS technology has improved significantly, thermal regulation remains unresolved:

“The range of the best scooter battery is far lower in January in cities like Chicago, Oslo, or Berlin than it is in July.”

Integrated Systems: Lime’s Approach

Lime operates year-round across cold-weather markets in North America and Europe, including Canada, the Nordics, and Central Europe. This long-term exposure shapes both design and operations.

Laura Ross, Program Manager of Policy & Codes at Lime, explains:

“Lime designs our entire battery ecosystem in-house, including the battery pack, BMS, and charging infrastructure. This integrated, system-level approach allows Lime to manage battery performance and safety across a wide range of real-world operating conditions.”

Lime’s BMS continuously monitors internal temperature, voltage, cell health, and state of charge. This allows the system to respond automatically to cold conditions rather than relying on manual intervention.

“The sophistication of Lime’s BMS allows us to account for colder temperatures at the system level, rather than relying on manual intervention or hardware alone.”

Cold-weather operation also reinforces the role of certification and testing. Lime designs and validates its systems against recognized safety standards, using third-party testing to ensure environmental stress does not compromise winter operation. Lime also tracks real-time winter performance data to inform future design and operational decisions.

“Design choices, testing, and certifications by Nationally Recognized Testing Laboratories help to prevent environmental stress from affecting winter operation.”

In Practice

Cold weather exposes the hard limits of lithium-ion batteries in micromobility. Chemistry defines those limits. Software, hardware, and operations decide how closely fleets can approach them without damage or failure.

Across the industry, winter reliability depends on strict charging controls, accurate BMS estimation, careful cell selection, added logistics time, and reduced operational efficiency. There are no shortcuts. Batteries that retain capacity after winter ultimately determine how long vehicles, and entire fleets, remain viable.

.svg)

%2Bcopy.jpeg)

.svg)