In a Berlin warehouse, a fleet of e-scooters is being carefully disassembled. Batteries are tested, frames inspected, and worn-out parts replaced. These aren’t broken vehicles bound for the scrap heap; they’re being given a new lease on life. Just a few years ago, these same machines were considered disposable, with lifespans often measured in just over a month.

Today, they are built to last for years. The modern shared e-scooter is designed as a durable asset, with leading operators now expecting their latest models to remain in service for up to fifteen years.

A Timeline of Progress

This wasn't always the case. The industry's initial foray into shared micromobility was marked by very short vehicle lifecycles. A stark example comes from Bird's launch in Louisville, Kentucky in 2018. An analysis of public trip data by Quartz revealed that the average lifespan of a Bird scooter in the city was just 28.8 days. These early models, often adapted from consumer-grade products, struggled to withstand the rigors of constant public use, weather, and vandalism. This extremely short lifespan created a devastatingly high carbon cost per ride and made it nearly impossible for operators to achieve profitability, as the substantial upfront manufacturing emissions and vehicle costs could not be offset by such a brief period of revenue.

Around this time, lifespans across the industry were typically measured in mere months. Shared micromobility operator Dott noted that their initial models were expected to last only about 18 months.

By 2021, improved hardware and better operational practices had extended lifespans to several years. Dott’s 2023 report highlighted this progress, noting that 90% of its refurbished Gen 2 e-scooter fleet was still deployable after four years, far exceeding the suppliers’ original life expectancy of 18 months. Similarly, by 2023, Voi reported that its primary scooter model had a lifespan of 6.25 years.

The current benchmark is even higher. Voi’s 2024 sustainability report states that its latest e-scooters and e-bikes are designed for a 15-year operational life. This represents a twentyfold increase over the company’s earliest models.

According to Åsa Christiander, Head of Sustainability at Voi, this dramatic increase is due to three key factors: more durable and modular vehicle design, better-trained operations teams, and improved data analytics. With better data systems, the company can now track each vehicle’s location, detect issues early, and reduce losses through proactive maintenance.

Vehicle lifetimes are measured by tracking monthly fleet losses to estimate how long it takes for half the fleet to retire. The recent data showed loss rates have dropped to very low levels, with many vehicles lasting well beyond expectations, often remaining in service for 5–6 years compared to the earlier 3–4 year average.

Fleet Growth and Usage

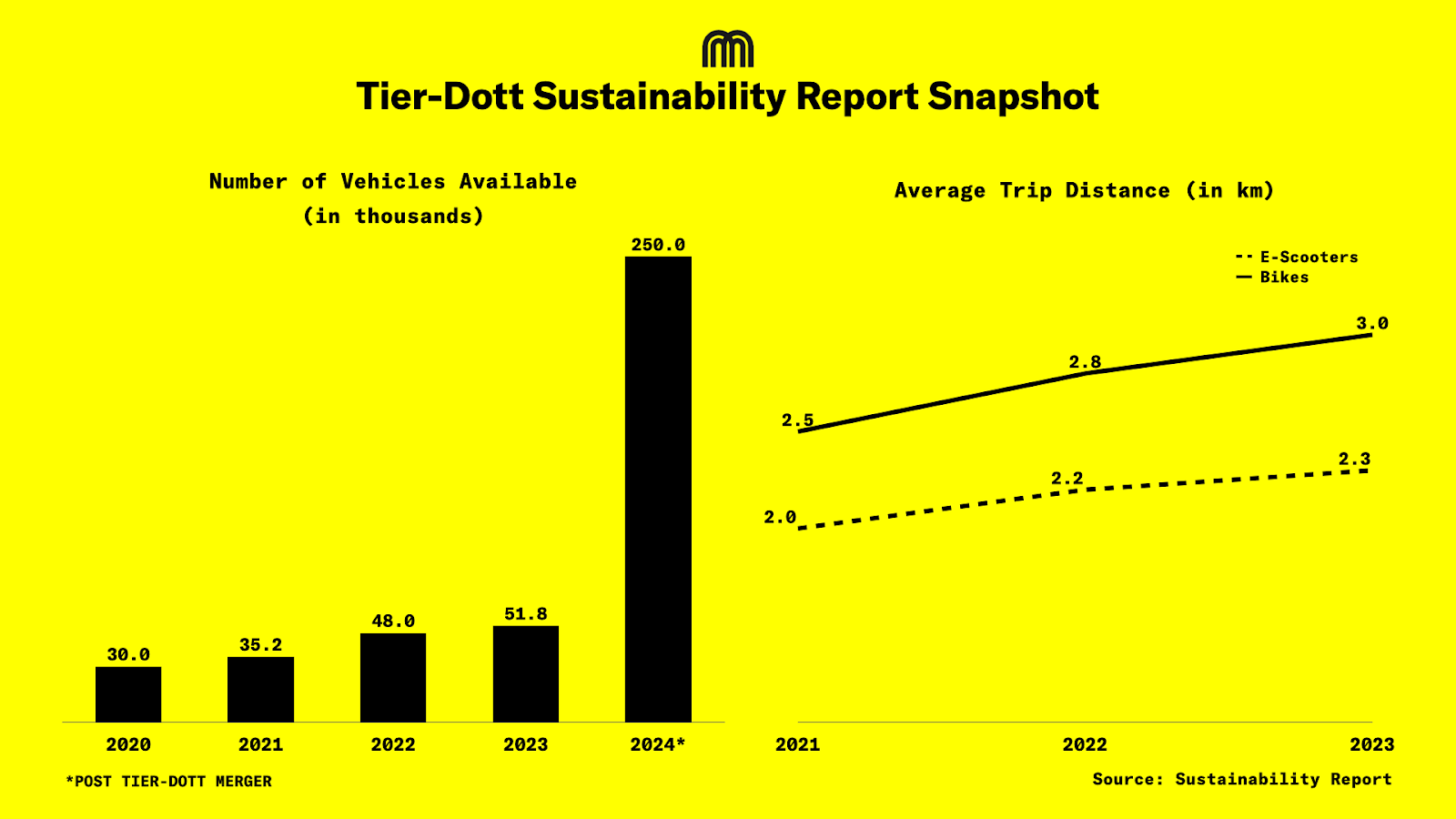

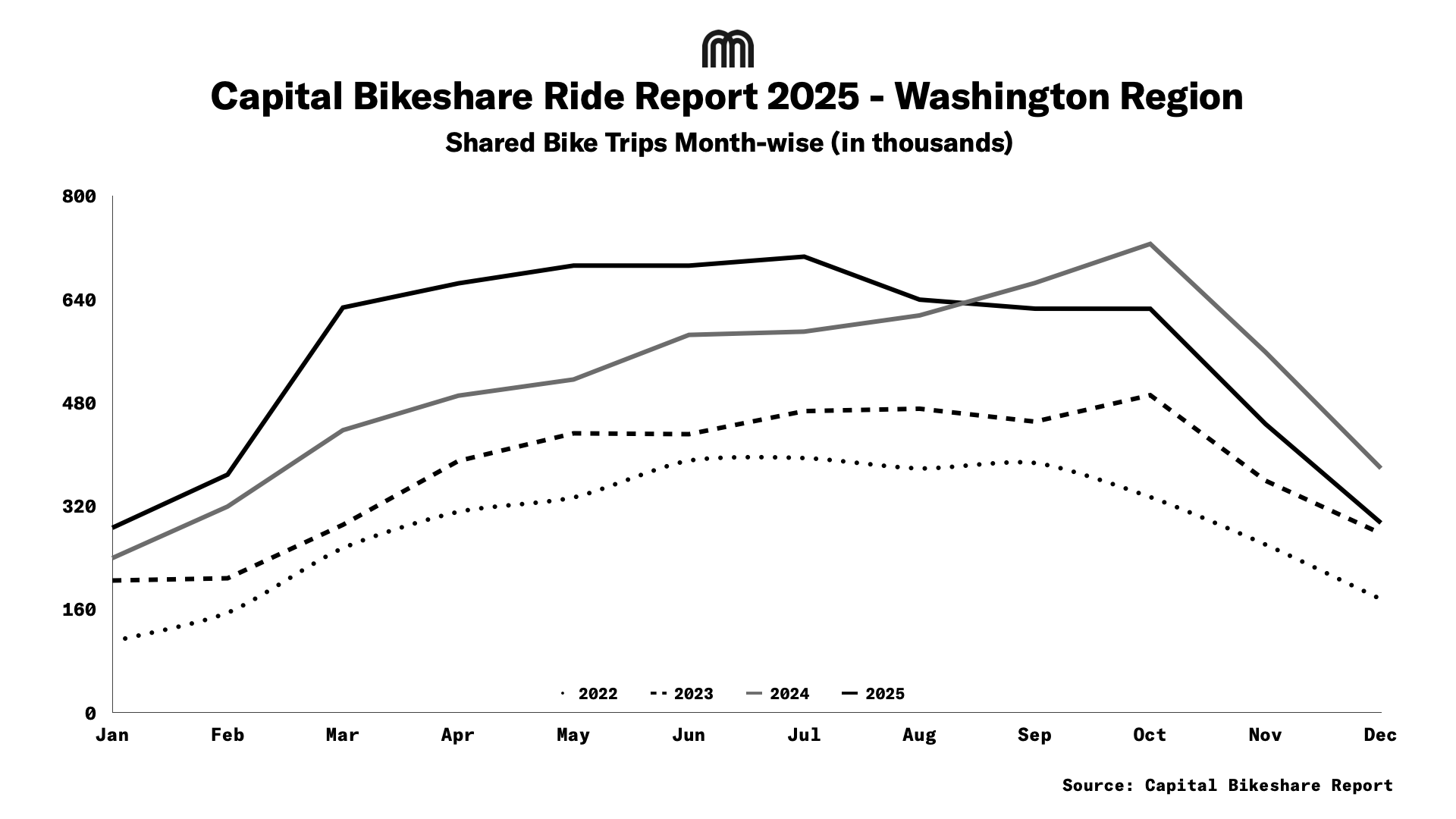

The scale and usage of shared micromobility services continue to grow. Following their merger, Tier-Dott has steadily expanded its combined fleet to 250k vehicles in 2024. During the same period, the average e-scooter trip distance increased by 40%, from 2.0 kms in 2020 to 2.8 kms in 2024, indicating a shift toward longer, more practical journeys.

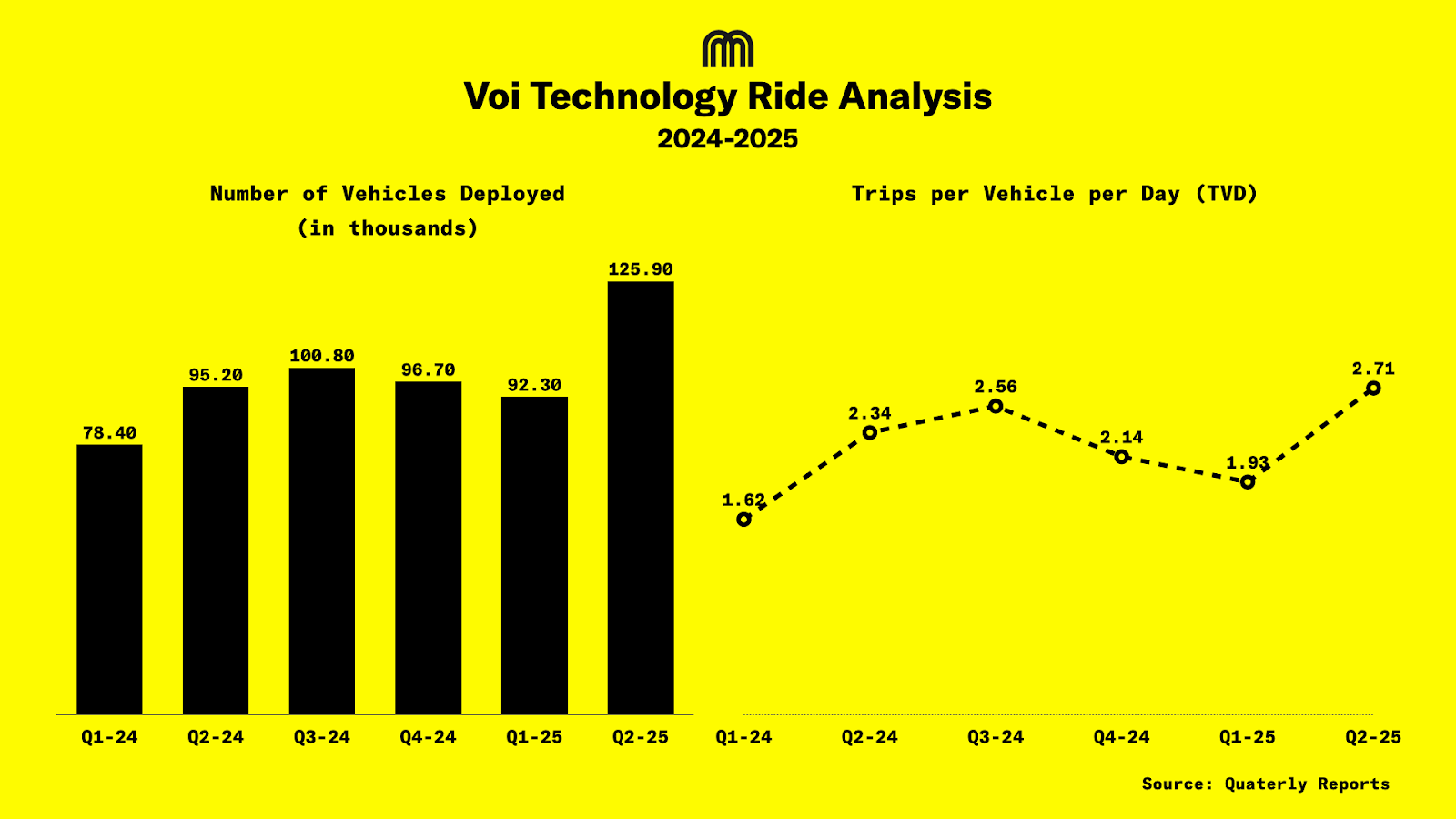

Similarly, Voi maintained a deployed fleet ranging from 78.4k to 125k vehicles throughout 2024 - 2025, with trips per vehicle per day (TVD) peaking at 2.71 in Q2 2025, demonstrating consistent utilization alongside fleet growth.

Voi provides specific data on the age of its fleet, highlighting the real-world results of these durability improvements:

"The average age of our scooter fleet is just under 4 years (3.8). We had a high fleet growth with our latest model, V8, introduced this year. Approximately 50% of our scooter fleet has been 5-6 years on the streets. Bikes are a rather new introduction to our business. The average bike age is 1.2 years."

Reliable usage at scale makes engineering durable, long-lasting vehicles both an environmental and commercial imperative.

What It Takes to Last Longer

Firstly, scooter hardware has evolved significantly. Early models were often adapted from consumer-grade products, whereas today’s shared scooters are engineered for durability from the ground up. They feature stronger frames, more reliable components, and modular designs that simplify repairs. As Dott noted, “More professional operations taking better care of fleet maintenance” and “more robust hardware” have been critical.

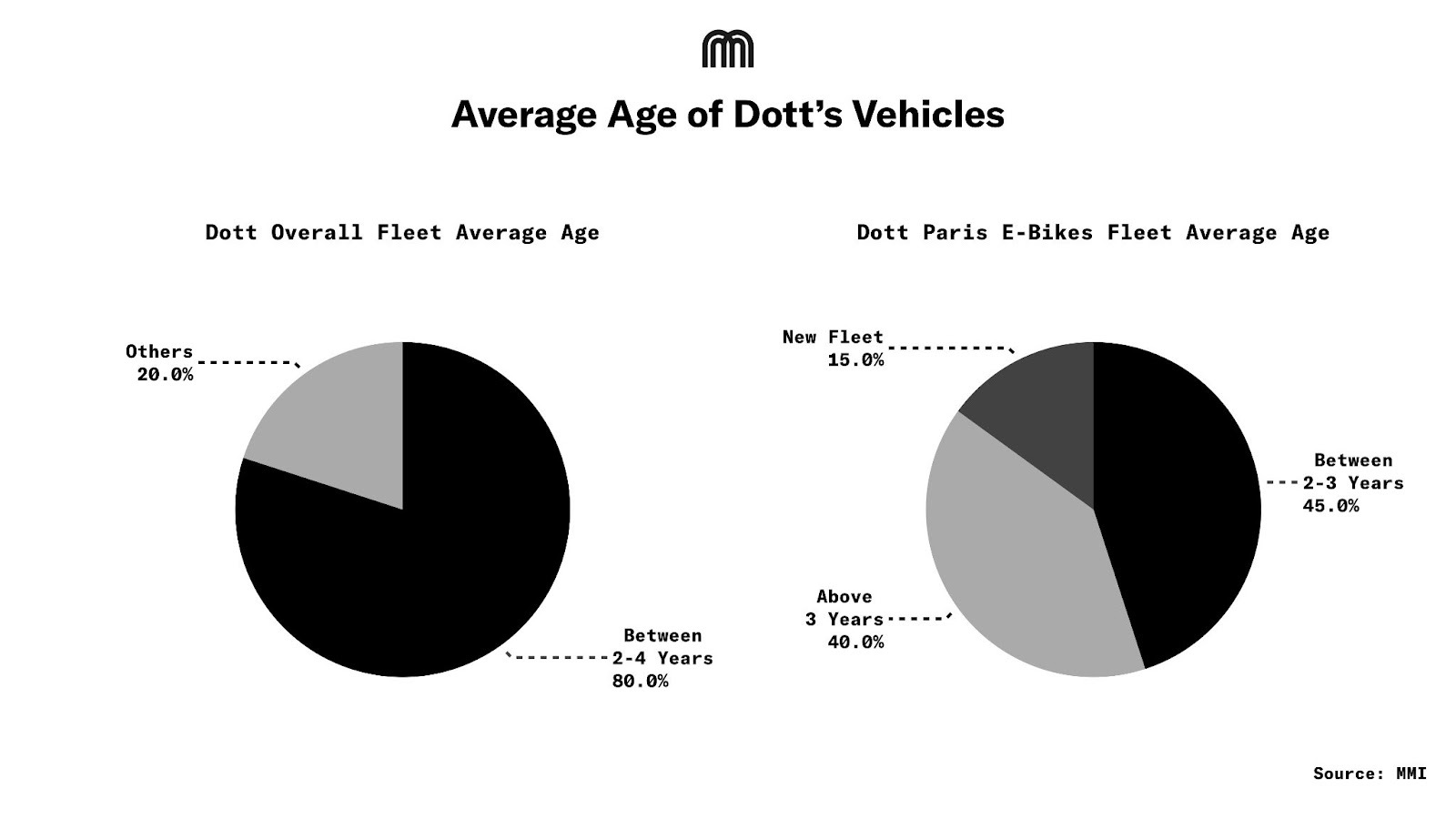

This is reflected in the real-world age of their fleets. Dott says that over 80% of its fleet is between 2 and 4 years old. Their current fleet in Paris (composed solely of e-bikes) is a testament to this: 15% of the fleet is new, while 45% of the e-bikes are between 2 and 3 years old.

This longevity is a key reason why lifecycle targets for different vehicle types vary. For instance, the target lifetime distance for e-bikes is often set much higher, at 20,000 km, compared to 12,000 km for e-scooters. TIER-Dott sheds light on this, noting that "Shared e-bikes often have a longer operational life due to their robust construction, featuring larger frames and wheels that are well-suited to handle diverse urban terrain."

Secondly, maintenance has become more sophisticated. Reactive repairs have been replaced by proactive, data-driven care. Operators now employ trained technicians who perform regular servicing and use diagnostic software to predict failures before they occur.

Another important aspect is the adoption of circular economy principles. Instead of discarding scooters at the end of their initial life, companies now extensively refurbish them. Voi gives its scooters a “second life” through complete refurbishment, while TIER-Dott’s “Phoenix” program has refurbished 25k vehicles to date, including 9.7k in 2024 alone. This process involves completely disassembling scooters, replacing worn parts, and returning them to service in like-new condition, effectively resetting their lifecycle.

This circular approach is applied with equal rigor to the scooter's most vital component: its battery.

Battery Longevity

Longevity extends critically to the battery, the most resource intensive component.

Voi reports that with careful charging and maintenance, its latest battery packs are expected to last the entire 15-year lifespan of the vehicle. Dott designs its batteries to last for seven years by following specific charging and maintenance protocols that optimize life and prevent capacity loss. When issues do arise, the response is repair rather than replacement. Voi highlights: "Our refurbishment partnerships have helped a lot. Previously, we scrapped batteries with repairable issues like faulty connectors. Now, partners like Nowos in France and County in the UK refurbish them, increasing expected battery lifespan to around 10 years." Similarly, TIER-Dott's reporting also cites its collaboration with Nowos for battery refurbishment.

For batteries that can no longer power scooters, a “second life” awaits. Companies like TIER-Dott partner with specialists to repurpose these batteries for less demanding applications, such as stationary energy storage. In one instance, decommissioned scooter batteries were used to power electric mopeds and a water buoy. This approach ensures that over 98% of batteries stay in circulation, according to Voi’s reporting. Dott aims to reuse or recycle 100% of its batteries.

Impact on Emissions

A scooter that lasts 15 years has a lower environmental impact per ride than one that lasts just one.

The link between longevity and lower emissions is direct. The production of a scooter, including extracting raw materials, manufacturing components, and assembly, accounts for the largest share of its total carbon footprint.

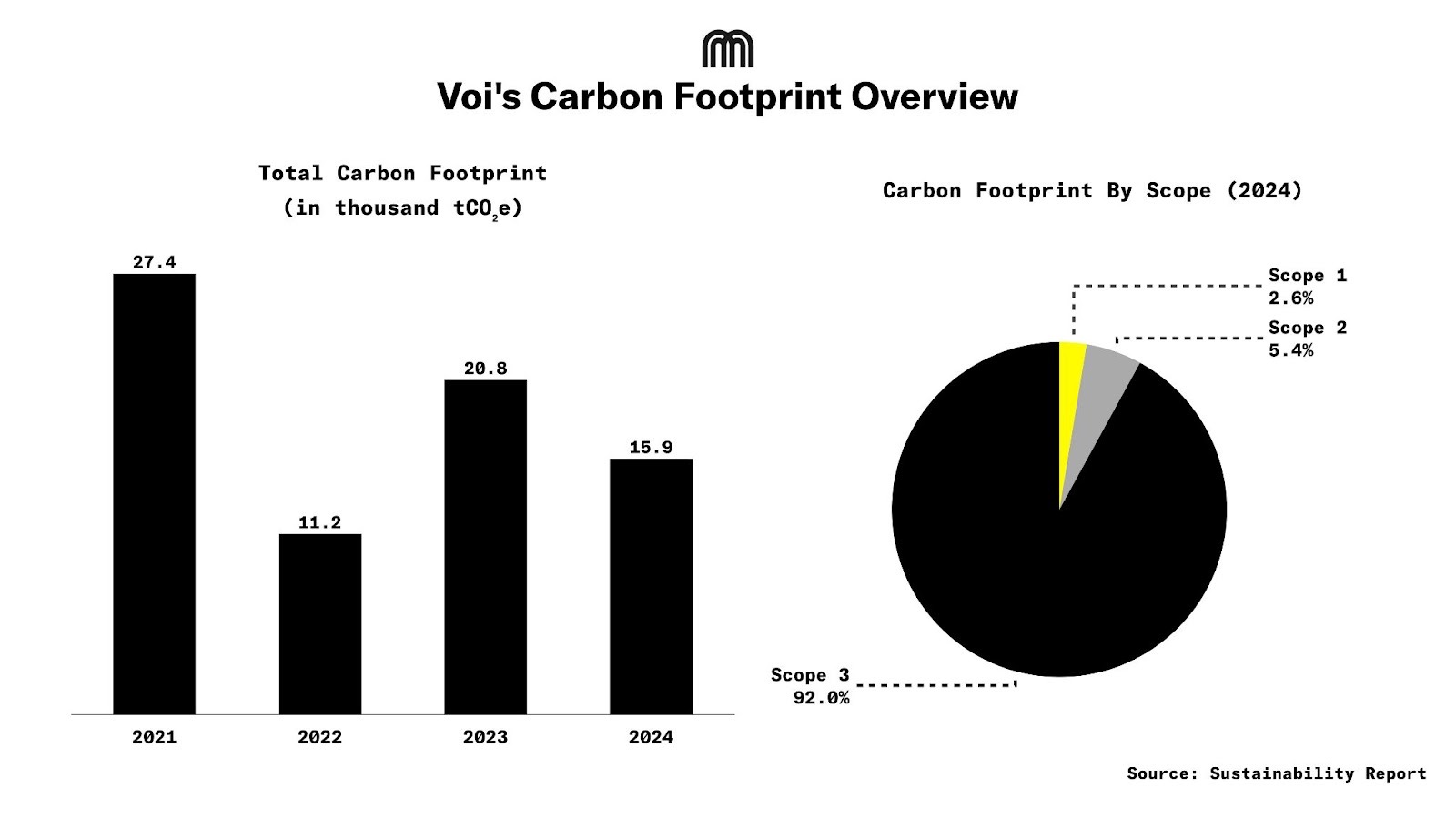

Voi’s sustainability reporting provides a clear breakdown of its footprint using the standardized "Scope" framework:

- Scope 1: Direct emissions from company-owned sources, such as the few remaining fossil-fuel vans used in fleet operations.

- Scope 2: Indirect emissions from purchased electricity (e.g., for charging vehicles and powering offices).

- Scope 3: All other value chain emissions, including manufacturing vehicles, transportation, and waste.

The fact that Scope 3 emissions constitute 92% of Voi’s footprint is key to understanding the environmental imperative of durability. A scooter discarded after just a few months results in a devastatingly high carbon cost per ride, as its substantial upfront manufacturing emissions are barely offset.

A 2023 study from University College London, using data from operator Voi, found that the carbon footprint of e-scooters is highly sensitive to their operational lifespan. The research concluded that while e-scooters with a short lifespan (around 3k kms) can increase net emissions, those with an average or long lifespan (6.5k kms and above) can reduce CO₂ emissions by up to 45.8% compared to the car trips they replace.

By extending a scooter’s operational life, these initial “embedded” emissions are spread across a much larger number of rides, thereby reducing the environmental cost per trip. Voi reports that the emission intensity of its service has fallen by 77% per kilometer since 2019, an achievement directly tied to vehicles lasting longer and incorporating more recycled materials.

Conclusion

The evolution of micromobility devices from short-lived products to long-lasting assets marks a significant shift. The focus is no longer on how many vehicles can be deployed, but on how long each one can last. When vehicles are built to last over a decade, they transition from being a temporary convenience to a genuine, low-emission alternative to car trips.

This proves that with the right design, maintenance, and a commitment to circular principles, we can build things that last.

Image credit/dott

.svg)

%2Bcopy.jpeg)

.svg)

-2.jpg)