Disruption, with a capital D, is a term of art defined by Clayton Christensen. He said that if a new technology enables a new business model that is sufficiently asymmetric to the incumbent, the incumbent will not attempt to do anything with it. But this new emerging business model will evolve rapidly.

Eventually this new model will overcome the performance limitations and take more and more share from the incumbent and the incumbent will abandon markets and choose to go up market. They will go to a more comfortable location where they can still make continuous profits.

When you look at the segmentation that I put forward from very short distances to very long distances, the automaker will gravitate towards long distances because and bigger vehicles and heavy vehicles and more long-range vehicles are the more profitable vehicles. They will abandon the short distances because they're not profitable. [As evidence consider that in the US Ford and GM have essentially abandoned cars in order to focus on SUVs and pick-up trucks—vehicles associated with rural and suburban travel and disassociated from urban travel.] So this is the classic Disruption where “from below” the scooter becomes a vehicle that is ready to expand its range and its capabilities. Eventually, the entrant takes on more and more kilometers. It begins with one kilometer then goes to 10, then to 15, then to 20.

The interesting thing about the distribution of trips however is that the vast majority are very short and, in fact, the distribution of trips is such that [I've done this calculation for the United States] if you were to take all the trips less than 12 miles they equal, in quantity, in value, in terms of dollars spent, all the miles above 12 miles. That is called the point of parity: at what distance does the value of transportation balance.

On the spectrum of distance that happens to be between 12 and 15 miles. I think in Europe is going to be closer to zero. Let’s say for the sake of argument it could be 15 kilometers. From an economic point of view, that means that there's as much value in the first 15 kilometers as there is in trips taken above that.

The dilemma is that the car will still be used for long distance travel. Supplying those kilometers will continue to be appealing and will sustain the car. Until it’s too late.

That’s because of the long-term pattern of urbanization. We have 75% of Europeans living in cities and that's going to grow globally. It's going to reach something like 60 to 70 percent by 2050. [Some say we’re already there.]

Urbanization drives the trend towards shorter distances and demand will grow for these types of trips. As a result my assumption is that a disruption will occur and and it'll come from the bottom. We'll see how long it takes. This is the whole debate. My analysis is mostly centered on how long it takes. Not whether it will happen, but whether it's going to be five years, 15 years and so on. What we have data on so far is from China. It was there that we saw mass adoption of undocked or free-float bike sharing systems. Of course dock-based systems have been around much earlier, but the difference between docked systems and dockless is that there's a lot more accessibility. It's the same difference between having personal transport; anywhere to anywhere system versus public transport, which is a Station-to-Station system.

And although there are many stations possible it is still much more restrictive than what we see with with dockless. So dockless has only been around for about two three years.

These ideas have been around. The very first system was in Amsterdam in the 70s. What has changed is that it became easier and more accessible, how the bicycle was locked and unlocked. With the Chinese system you use your phone to unlock the bike because it has communication.

And then came the scooter systems, which are actually all the rage now. Only they are one year old and began in September of 2017. In the US two companies are having the largest market share today. They are Lime and Bird. Bird was the first to deploy.

Again, they were not the first-ever. There was a Singapore system that was the very first. But it was in the US that it became quite a big hit. These two companies both registered 10 million rides in the first year. So in about 12 months these systems were able to get to that number.

And of course they were fed by venture capital and therefore many of these vehicles were made available quickly. And that enables of course the large number of users. The Chinese system as of February of this year was cited as having 400 million registered users 70 million daily active users and a fleet of about 23 million bikes. [By the time of writing, many of these Chinese bikes became stranded assets as they were “retired” due to over-capacity.]

So in three years the Chinese system gained these numbers and these are numbers that are on the scale of Facebook. Bike sharing has been growing as fast or even faster than social media and when you look at the rate of growth of the scooter sharing, it's on the same scale as Android or iPhone—actually probably even faster.

We're not measuring the exact same quantity because one is in users and devices sold, the others in terms of rides. But I've put together the data that shows how these curves look and there's a sort of a pattern to these curves and you can see that the speed of adoption of these vehicles now again, after one or three years we're looking at very, very short time frames.

So here we are 10 million rides in one year for one of these companies. So it's about timing. We have to ask how fast is it going, and how big can it get?

In the US alone there are about 371 billion person trips taken every year and 2 trillion vehicle miles traveled. Globally the “market for miles” is 52 trillion km of which I estimate 27 trillion are automobile km (a bit more than half). Very short distance addressable market is further estimated to be about 4 trillion km or 2.5 trillion miles based on the log-normal distribution of US VMT. So if you assume that the addressable market is about half of that then you have to ask how quickly will these systems generate 1 trillion miles, and, at 1 mile average distance per trip, a trillion trips a year. So we're at 20 million and there many zeros left to go.

Fortunately they grow logarithmically. We cannot add 10 million every year, that will take forever. We need the addition of one zero every year. So in other words, rides are increasing by tenfold every year.

It’s not likely to grow quite that fast but still we can make some estimation that this is maybe on the 10-year cycle not a 20 year cycle.

This is happening in America which is where the car is king and it's Los Angeles where the car is even more king. The car dominates society and infrastructure is not even available for micromobility vehicles. Furthermore, the people who use them are taking their lives in their hands because they are not using helmets. They are riding on streets with cars.

Cities are in a panic in many cases, but it's happening. It's happening very quickly. And in China we had a different phenomenon. 400 million people is not a small number; 70 million a day every day is a huge number.

And so this demand was created in no time. Now, some of the businesses may not be sustainable but I would bet they will be replaced by something even bigger because this phenomenon is genuine.

This is not just a fad. People are not doing this only for fun. They're doing it because they are getting utility out of it. There are many small vehicles used for fun. You can roller-skate, you can rollerblade, you can use a mountain bike to go up and down on a mountain. Or you can use a snowmobile in the woods. These are micro vehicles in the same sense of low weight. But they're not used for utility. They've been around for a long time, so their growth is very low, but in micromobility we have a vehicle that's used for utility purposes, that is, to get around.

Micromobility is popular across age groups. Across gender, across demographics so in every city, wherever they're put in use, they are very popular. I think the evidence is overwhelming that whether it's a cycle or electric bicycle or a docked or dockless, or throttle based, two or three wheels, micromobility is resonating with users and there's still plenty of room to go.

I'm thinking there are ten years before we reach saturation and it will take a chunk of existing trips. Even if we only look at distances less than 5 km.

I don't want to exaggerate but for the car industry to lose the first five kilometers, car utilization and necessarily car sales will begin to be affected significantly. It’s not an existential crisis. Not yet anyway. It’s like saying if you have a smartphone do you use your computer?

Of course you still use your computer, but you start to use your phone for short tasks where the computer is maybe not the best because it's “over-serving.” If you want to text someone or even respond to an email quickly you're going to use your phone, but you can see the impact of the phone on the computer industry. PC sales started declining in 2010. Three years after the iPhone launched.

The result is that Microsoft has had to change its business model to be a services company and not strictly selling software anymore.

So this is the question for carmakers again, they might need to switch their business the way Microsoft did perhaps by selling cars as a service. But if they don't there will be a crisis in a decade.

Theory predicts exactly how this happens but it doesn't mean that those who know the theory can do anything about it. That's why it's called a dilemma.

The temperature is rising but car makers don't feel the pain immediately and indeed for a long time, it will feel better. It feels better because it encourages you to abandon less profitable markets. Let me give you the example of Ford.

So Ford in the United States is going to sell only pickup trucks and SUVs. Except for sports cars (the Mustang), they're abandoning the sedan market. Smaller cars, hatchback and so on, are unattractive to Ford. These are not profitable businesses because these products have low margins. [GM followed with a similar strategy.]

Essentially Ford is “fleeing” the urban market. But they are not the only maker feeling compelled to do so. Look at Mercedes or at any of the car makers and ask them, “What is your most profitable segment?” They'll say SUV. Even Volvo, even sports car brands like Porsche, Ferrari and Lamborghini are making SUVs.

In terms of defining performance as “distance of travel” or “habitat”, they're fleeing upmarket: bigger, ex-urban and designed for long distance travel. It's the place to go right now and it applies whether they're electric or not. Makers like Tesla are selling long range cars and the longer the range the more popular they are. Other makers will follow with this model because it's more profitable.

If you ask someone who's making a pickup truck or someone who's making the greatest SUV, whether it's a Volvo or Jaguar or Mercedes: “How about a bicycle?” “How about a scooter?”

You can see how the answer goes. You go upmarket easily but downmarket feels wrong.

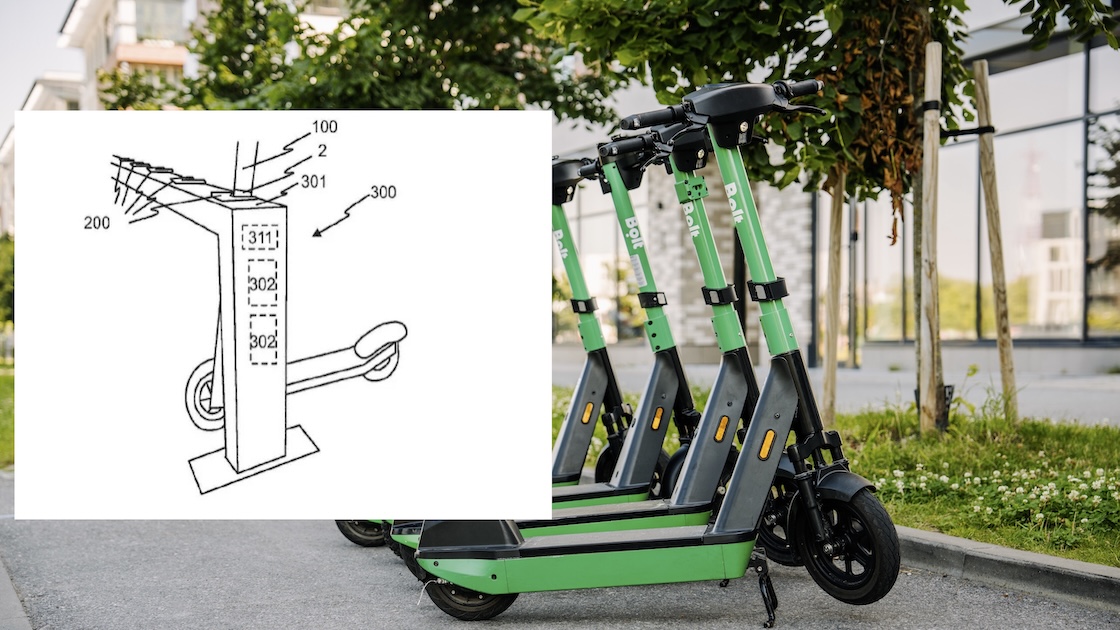

In contrast consider how a scooter company decides to evolve their product. What does this scooter company do next after deploying 10,000 of the first generation in a few months. They're going to evolve the vehicle to something more more robust. They're going to have a bigger battery. They’ll be motivated to improve their operating margins and that involves extending the lifespan and lowering charging costs.

They're going to have a bigger motor. They're going to be looking at ABS. They're going to be looking at traction control. They're going to be looking at stability control. They're going to add technology into the vehicle on three-month cycles.

Three months not three years. So in three months you have to change the fleet. It seems like a bad thing, but it's actually paying for itself. Hopefully you replace it with something better. And so the evolutionary cycle takes off. As an organism, it’s like a virus or a flea or a fly. It lives so quickly that it's able to evolve more quickly than an elephant.

That's one of the characteristics of disruption: the entrant is far more agile than the incumbent and is able to “eat” its opponent.

We live through this over and over again. We saw it with the microcomputer (as it was called before the Personal Computer]. IBM and Digital Equipment Corporation had been studying the Computing market for decades. It didn't matter. They did not harness the personal computer.

Or you could have seen it with the phone business and telecommunication companies which were looking at both cellular and fixed lines and making plans.

But the smartphone came and everything changed. We don't talk on them much anymore, we look at them. And that meant that none of those conversations about voice Communications were interesting anymore.

And it is the same thing going to happen with autonomy. Autonomy engineers are trying to make an existing system better, that existing system being cars on streets. But the car is not the subject matter. The car is a bundle of trips. It is a bundle of trips ranging from a few hundred meters and a few hundred kilometers that we prepay for.

And if you understand that then you realize the value in unbundling.

.svg)

%2Bcopy.jpeg)

.svg)

.jpg)